When your portal vein gets blocked by a blood clot, it’s not just a minor issue-it’s a silent threat to your liver, intestines, and overall survival. Portal Vein Thrombosis (PVT) doesn’t always cause obvious symptoms. Some people feel nothing until they collapse from intestinal ischemia. Others are diagnosed by accident during a scan for something else. But here’s the truth: if you catch it early and treat it right, your chances of living a normal life jump from under 40% to over 85%. That’s not a guess. That’s from real data tracked by the National Center for Biotechnology Information in 2023.

What Exactly Is Portal Vein Thrombosis?

The portal vein is the main highway carrying blood from your intestines to your liver. When a clot forms inside it-whether partially or fully blocking the flow-you’ve got PVT. It can happen suddenly (acute) or build up over time (chronic). Acute cases are more treatable. Chronic ones often mean your body has already started rerouting blood through tiny collateral vessels, a process called cavernous transformation. That’s harder to reverse.

It’s not just about the clot. Underlying causes matter. In non-cirrhotic patients, up to 30% have a hidden blood clotting disorder-like Factor V Leiden or prothrombin gene mutation. In cirrhotic patients, it’s usually the liver disease itself: slow blood flow, inflammation, and abnormal clotting proteins. Cancer, especially liver or pancreatic, is another major trigger. And yes, even recent abdominal surgery or infection can set it off.

How Is It Diagnosed?

Ultrasound is your first step-and it’s surprisingly good. Doppler ultrasound picks up PVT with 89-94% accuracy. It shows if blood is flowing normally or if there’s a blockage. If the clot is unclear, doctors move to CT or MRI with contrast. These scans show exactly how much of the vein is blocked: less than half, most of it, or completely sealed off.

Doctors also check for signs of complications. Are your varices enlarged? Is your spleen swollen? Is fluid building up in your belly? These clues help decide how urgent treatment is. A key detail: if you have cirrhosis, you need an endoscopy before starting any blood thinners. Why? Because if you have bleeding varices and you start anticoagulation without treating them first, you could bleed out.

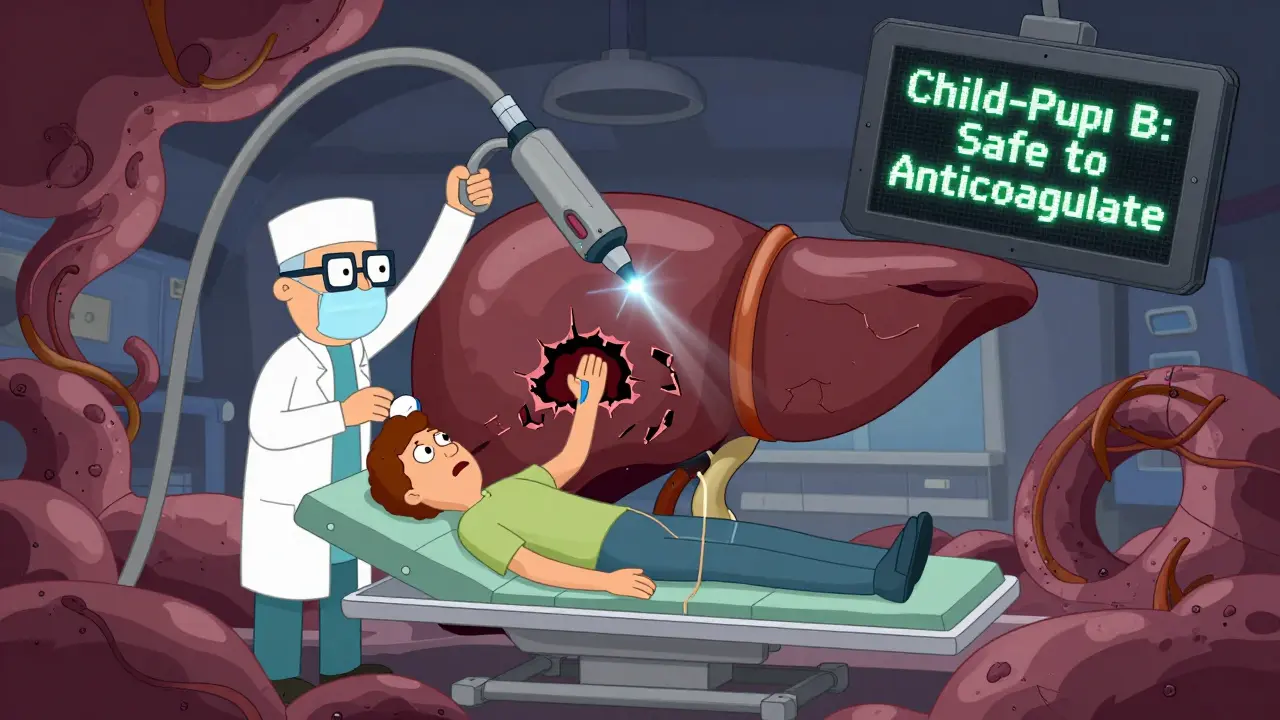

There’s no single blood test for PVT. But labs help. Low platelets? High INR? Abnormal liver enzymes? All of these feed into your risk profile. The Child-Pugh score and MELD score aren’t just jargon-they tell you how much liver function you have left, and that directly affects what treatments are safe.

Why Anticoagulation Isn’t Optional Anymore

For years, doctors were scared to give blood thinners to people with liver disease. The fear was bleeding. But the data has flipped. Today, major liver associations-AASLD and EASL-agree: unless you’re actively bleeding or in end-stage liver failure, anticoagulation should be started.

Why? Because untreated PVT leads to three big dangers:

- Intestinal ischemia-your bowel doesn’t get enough blood, and parts can die.

- Worsening portal hypertension-more pressure in your liver’s blood vessels, leading to more varices and more fluid buildup.

- Blocking liver transplant eligibility-if the clot grows, you might be taken off the transplant list.

Studies show that patients who start anticoagulation within 30 days have a 78% chance of partial or full clot resolution. Those who wait? Only 42%. That’s a massive difference. And if you’re planning a liver transplant, anticoagulation can boost your one-year survival after surgery from 65% to 85%.

Which Blood Thinners Work Best?

Not all anticoagulants are equal for PVT. Your choice depends on whether you have cirrhosis and how bad it is.

For non-cirrhotic patients: DOACs are now first-line. Rivaroxaban (20 mg daily), apixaban (5 mg twice daily), and dabigatran have shown better clot resolution rates than warfarin. In one 2020 study, rivaroxaban led to 65% complete recanalization. Warfarin? Only 40-50%. DOACs are easier-no weekly INR checks, fewer food interactions, and lower risk of brain bleeds.

For cirrhotic patients (Child-Pugh A or B): LMWH (like enoxaparin) is still preferred. Why? It’s predictable, doesn’t rely on liver metabolism, and has fewer drug interactions. Dosing is based on weight: 1 mg/kg twice daily or 1.5 mg/kg once daily. Target anti-Xa levels should be 0.5-1.0 IU/mL. Studies show 55-65% recanalization with LMWH versus 30-40% with warfarin.

For Child-Pugh C? Avoid anticoagulation. The bleeding risk is too high. That’s not a recommendation-it’s a warning. The FDA has a black box warning for DOACs in severe liver impairment. If you’re in this group, focus on managing complications: diuretics for fluid, banding for varices, and close monitoring.

And here’s a critical tip from UCSF: Always do endoscopic variceal ligation before starting anticoagulation in cirrhotic patients. Their 2022 study showed major bleeding dropped from 15% to 4% when they did this first.

How Long Do You Need to Stay on Blood Thinners?

It’s not one-size-fits-all.

- If your PVT was caused by a temporary issue-like recent surgery or infection-and it’s resolved, treat for at least 6 months.

- If you have an inherited clotting disorder (found in 25-30% of non-cirrhotic cases), you’ll likely need lifelong therapy.

- If you have active cancer, anticoagulation continues as long as the cancer is active.

- If you’re on the transplant list, you usually stay on it indefinitely to protect the new liver.

Recheck your clot with imaging every 3-6 months. If the clot is shrinking, you’re on track. If it’s growing or not changing, your team may need to adjust your dose or switch drugs.

When Anticoagulation Isn’t Enough

Some patients don’t respond. Or they can’t tolerate blood thinners. That’s when you look at other options.

- TIPS (Transjugular Intrahepatic Portosystemic Shunt): A metal tube placed inside the liver to bypass the clot. Success rate: 70-80%. But 15-25% of patients develop hepatic encephalopathy afterward. It’s a last resort.

- Thrombectomy: A catheter is threaded in to physically suck out the clot. Works in 60-75% of cases, but only available at major centers. Used for acute, massive clots.

- Surgical shunts: Rare now. Too invasive. Only considered if everything else fails.

These aren’t replacements for anticoagulation. They’re backups. And they’re expensive. TIPS costs more than $30,000 in the U.S. and requires a team of interventional radiologists and hepatologists.

What’s Changing in 2026?

The field is moving fast. In January 2024, AASLD updated its guidelines to allow DOACs in Child-Pugh B7 patients-something that was off-limits just two years ago. The CAVES trial showed DOACs were just as safe and effective as LMWH in this group.

And then there’s the new drug, abelacimab. It’s in phase 2 trials (NCT05214572) and could be a game-changer. It targets clotting proteins directly without affecting overall blood thinning. If it works, it might help cirrhotic patients who can’t take traditional anticoagulants.

Also, reversal agents like andexanet alfa are now FDA-approved for DOACs. That means if someone on rivaroxaban bleeds badly, doctors can quickly neutralize the drug. That’s huge for safety.

By 2025, experts predict DOACs will be used in 75% of non-cirrhotic PVT cases and 40% of compensated cirrhotic cases. That’s a dramatic shift from just five years ago.

What You Need to Do Right Now

If you’ve been diagnosed with PVT:

- Confirm the diagnosis with Doppler ultrasound.

- Get a liver function score (Child-Pugh or MELD).

- Have an endoscopy to check for varices-especially if you have cirrhosis.

- Ask for a thrombophilia workup if you’re under 50 and don’t have cirrhosis.

- Start anticoagulation within 30 days if your liver function allows it.

- Don’t wait. Delaying treatment cuts your recanalization chance in half.

If you’re a caregiver or family member: learn the warning signs-sudden abdominal pain, vomiting blood, black stools, confusion. These mean emergency care is needed.

Final Reality Check

PVT is not rare. Around 250,000 people in the U.S. get diagnosed each year, and that number is rising. But only 35% of general gastroenterologists feel confident managing it. That’s why many patients slip through the cracks.

The good news? The tools are here. The guidelines are clear. The outcomes are proven. You don’t need a miracle. You need action. Diagnosis. Anticoagulation. Monitoring. That’s the chain. Break any link, and the risk climbs. Nail all three, and you’re not just surviving-you’re living.

Jay Clarke

January 19, 2026 AT 10:25This is why I stopped trusting doctors. They act like PVT is some new discovery, but my uncle died from this in 2018 and no one even mentioned anticoagulation until it was too late. Now they’re acting like it’s common sense? Nah. It’s just profit-driven guidelines dressed up as science. They’ll push DOACs until someone bleeds out and then blame the patient.

Selina Warren

January 19, 2026 AT 20:12STOP WAITING. Seriously. If you’ve got PVT and your liver’s still working, start the blood thinners TODAY. I’ve seen people die waiting for ‘the right time’-there is no right time. The only right time was yesterday. Your liver doesn’t care about your fear. It just wants blood to flow. Don’t be the person who reads this after it’s too late. Move. Now.

Robert Davis

January 21, 2026 AT 09:52Interesting. But have you considered that the 85% survival rate might be skewed by selection bias? Most studies only include patients who are already stable enough to receive anticoagulation. What about the ones with decompensated cirrhosis and multiorgan failure? They’re rarely included. And if you’re one of them, your ‘chances’ are basically zero. The data looks good until you realize it’s not for everyone.

christian Espinola

January 22, 2026 AT 20:38Correction: The National Center for Biotechnology Information doesn't track survival rates. It's a database. The data comes from journals like Gastroenterology or Hepatology. Also, 'cavernous transformation' is misspelled in the post-it's 'cavernous transformation,' not 'cavernous transformation.' And 'DOACs' shouldn't be capitalized unless it's the start of a sentence. This post reads like a med student's draft with a thesaurus.

Chuck Dickson

January 23, 2026 AT 09:27Hey everyone-this is the kind of info that saves lives, and I’m so glad someone took the time to lay it out like this. If you’re reading this and you or someone you love has been diagnosed with PVT, don’t panic. But DO act. Talk to your hepatologist. Ask about the endoscopy. Ask about the DOACs. Ask about the timeline. You’re not alone. There’s a whole community out here rooting for you. You’ve got this.

Dayanara Villafuerte

January 24, 2026 AT 02:38So basically: if you’re not cirrhotic → DOACs ✅

if you’re Child-Pugh A/B → LMWH ✅

if you’re Child-Pugh C → pray and hope your spleen doesn’t explode 🤞

Also, abelacimab sounds like a villain in a Marvel movie. Can’t wait for Phase 3. 🧪💉

Andrew Qu

January 25, 2026 AT 14:07Just wanted to add a real-world note: I’m a nurse in GI, and I’ve seen patients on rivaroxaban for PVT for over 2 years with zero bleeding. They’re hiking, working, cooking for their grandkids. The fear of bleeding is real-but the fear of *not* treating is deadlier. If your doc hesitates, ask for the AASLD guidelines. Print them. Bring them. Be your own advocate.

rachel bellet

January 26, 2026 AT 04:37There’s a fundamental flaw in the assumption that anticoagulation is universally beneficial. The MELD score doesn’t account for portal vein patency as an independent mortality predictor-yet the entire treatment paradigm hinges on it. Moreover, the 78% recanalization statistic is from a single-center retrospective cohort with <50 patients. This isn’t evidence-based medicine-it’s guideline-based wishful thinking. And don’t get me started on the conflict of interest in the DOAC industry funding these trials.

Eric Gebeke

January 26, 2026 AT 08:19So you’re telling me the same doctors who told me not to take aspirin for a headache now want me on blood thinners for life? And you think I’m gonna trust them? I’ve seen what happens when they ‘monitor’ people. It’s just a waiting room with a stethoscope. I’m not starting anything until I’ve seen the raw data from every trial they’re quoting-and I’m not talking about abstracts. I mean the full datasets. Open access. No redactions.