When you keep getting sneezes after eating peanuts, or your skin breaks out every time you walk past a grassy field, it’s not just bad luck. You might be dealing with an IgE-mediated allergy. But how do you know exactly what’s triggering it? That’s where specific IgE testing comes in. This blood test doesn’t guess - it measures your body’s immune response to individual allergens, giving doctors a clear picture of what you’re truly allergic to.

What Exactly Is Specific IgE Testing?

Specific IgE testing, sometimes called allergen-specific IgE or sIgE, measures the amount of immunoglobulin E (IgE) antibodies in your blood that react to a single allergen. IgE is the antibody your immune system produces when it mistakes something harmless - like pollen, milk, or dust mites - for a threat. When this happens, your body releases chemicals like histamine, which cause allergy symptoms.

This test isn’t new. Back in the 1970s, doctors used the RAST test, which could only say “yes” or “no” to whether you had an allergy. Today, we use much more precise methods like ImmunoCAP, which gives a number in kUA/L units. This number tells you not just if you’re allergic, but how strongly your immune system reacts. A result of 0.35 kUA/L or higher is considered positive. But here’s the catch: a higher number doesn’t always mean worse symptoms. It just means more antibodies are floating around in your blood.

How Is the Test Done?

It’s a simple blood draw. You don’t need to fast. You don’t need to stop your medications (unlike skin testing, which requires you to pause antihistamines for days). A technician draws about 2 mL of blood into a yellow-top tube. That’s it. The sample goes to the lab, where it’s tested using Fluorescence Enzyme Immunoassay (FEIA) - the gold standard method used by most labs today.

Most labs run these tests daily. You’ll usually get results back in 3 business days. Some rare allergens might need to be sent to specialized labs, which can take longer. The test can check for dozens of allergens - from common ones like cat dander and peanuts, to less obvious ones like latex or certain spices.

What Do the Numbers Mean?

Results come in two forms: a number (kUA/L) or a grade from 0 to 6. Here’s what they mean:

- 0 (less than 0.35 kUA/L) - Negative. No detectable IgE antibodies to that allergen.

- 1 (0.35-0.69 kUA/L) - Low. Possible sensitization, but not necessarily clinical allergy.

- 2 (0.70-3.49 kUA/L) - Moderate. Likely to cause mild symptoms.

- 3 (3.50-17.49 kUA/L) - High. Strongly associated with allergic reactions.

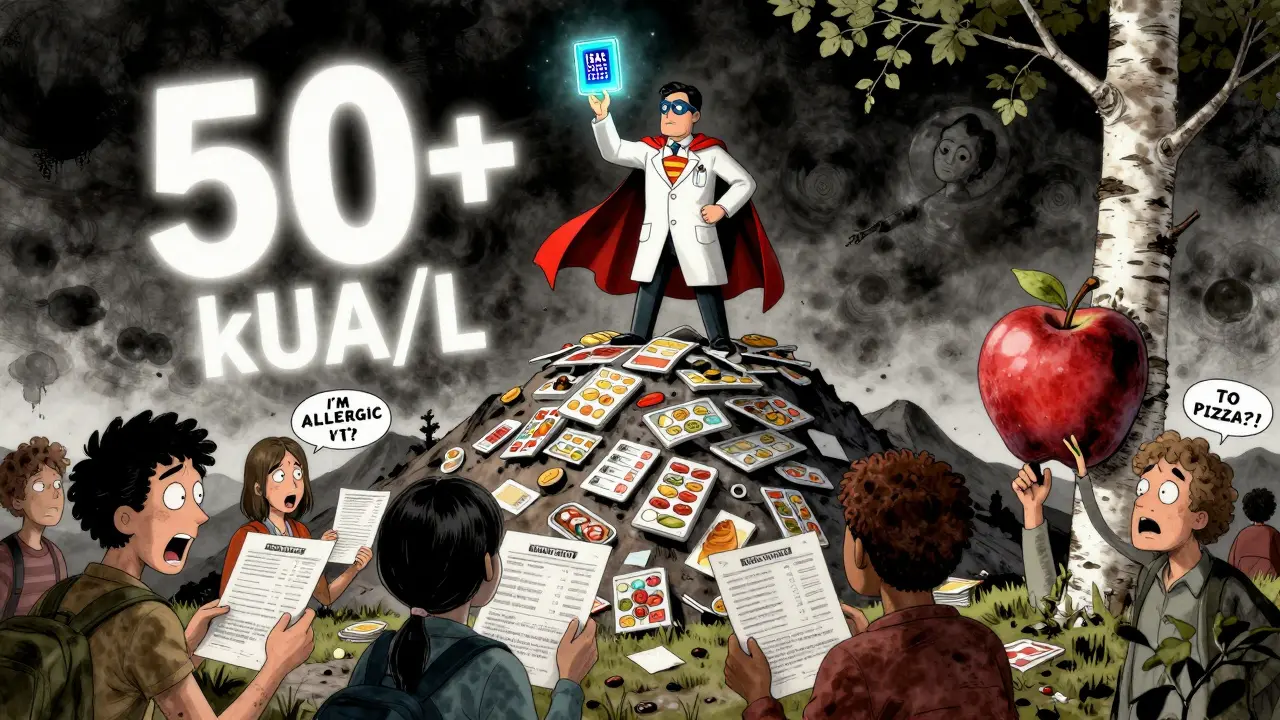

- 4 (17.50-49.99 kUA/L) - Very high. Almost always causes symptoms.

- 5-6 (50+ kUA/L) - Very high. High risk of severe reactions like anaphylaxis.

But here’s where people get confused. A result of 0.5 kUA/L might mean nothing if your total IgE is 100 kUA/L. That’s because your body is already producing a lot of IgE for other reasons - maybe you have eczema or chronic sinusitis. In that case, 0.5 kUA/L is just a drop in the ocean. But if your total IgE is only 2 kUA/L, then 0.5 kUA/L is a big deal - it’s 25% of your total. That’s why labs now automatically check total IgE when a specific IgE comes back positive. It helps doctors make sense of the numbers.

When Is This Test Used?

Specific IgE testing isn’t a first-line tool. Skin prick testing is usually preferred because it’s faster, cheaper, and shows real-time reactions in your skin. But there are clear situations where blood testing wins:

- You’re on medications like antihistamines, antidepressants, or beta-blockers that interfere with skin tests.

- You have severe eczema covering more than 40% of your body - skin testing isn’t practical.

- You’ve had a serious reaction to a food or insect sting, and doctors want to avoid risking another reaction during testing.

- You’re a young child with extreme fear of needles or skin pricks.

In fact, about 27% of pediatric patients in the U.S. get blood tests because they can’t stop their antihistamines for the 72-120 hours needed before skin testing. For those with severe eczema, skin testing is often too painful or unreliable.

What About Food Mix Tests?

Some clinics still offer “food panels” - testing for peanut, tree nuts, milk, egg, soy, and wheat all at once. Don’t fall for it. The National Guideline for Laboratory Testing (2025) says these panels are a bad idea. Why? Because they generate false positives over 30% of the time. If you test for 20 allergens, you’re almost guaranteed to get a few positive results - even if you’ve eaten those foods your whole life without problems.

Instead, testing should be targeted. If you get hives after eating cashew, test for cashew. Not for all tree nuts. If you react to pollen in spring, test for birch, not every weed and grass. Doctors should ask: What happens? When? And what triggers it? If you’ve never had a reaction to milk, don’t test for it just because it’s “common.”

Component-Resolved Diagnostics: The New Frontier

Modern testing is getting smarter. Instead of testing for whole allergens like “peanut extract,” labs now test for specific proteins inside them - like Ara h 2 for peanut. This is called component-resolved diagnostics (CRD).

Why does it matter? Because not all peanut proteins cause the same reactions. Ara h 2 is linked to severe, life-threatening allergies. But another protein, Ara h 8, is similar to birch pollen. If you’re allergic to birch, you might test positive for peanut - but only get mild mouth itching (oral allergy syndrome). CRD can tell the difference. Studies show specificity jumps from 70% with traditional tests to 92% with CRD for nuts.

Some labs now use multiplex chips like ISAC that test for 112 allergen components from one tiny blood sample. But these aren’t for general use. They’re complex, expensive, and require an allergy specialist to interpret. Right now, they’re mostly used in research or specialized clinics.

Why You Shouldn’t Test Without a Reason

Here’s the hard truth: about 22% of specific IgE tests ordered in primary care are unnecessary. That means one in five people get tested without a clear reason - and end up with confusing, scary results.

Dr. Robert Boyle, a pediatric allergy expert in London, says: “Only test when the result will change what you do.” If you’re not going to avoid the food, start immunotherapy, or carry an epinephrine pen - then why test?

And here’s another thing: if you’ve eaten a food for years without a problem, and then suddenly get tested, you might get a false positive. That’s why the National Guideline says 38% of inappropriate testing happens when patients with documented tolerance are retested. If you’ve eaten shrimp every Friday since you were 5, don’t test for shrimp just because you’re worried.

How Do Results Guide Treatment?

A positive test doesn’t mean you have to avoid everything forever. It’s a clue, not a sentence.

For example:

- If your peanut IgE is 15 kUA/L, your risk of anaphylaxis is over 95%. Avoidance and carrying an epinephrine auto-injector are critical.

- If your egg IgE is 0.6 kUA/L and you’ve eaten eggs without issue, you’re likely not allergic. Reintroduction under supervision might be safe.

- If your birch pollen IgE is high and you get itchy mouth from apples, you might benefit from allergy shots (immunotherapy) for birch - which can also reduce your apple reaction.

Testing can also guide immunotherapy. If you’re allergic to ragweed and have a high IgE level, you might be a good candidate for allergy shots. But if your IgE is low and your symptoms are mild, lifestyle changes might be enough.

What’s Next After the Test?

Don’t look at your results alone. Take them to an allergist. They’ll combine your test numbers with your history: when symptoms started, what you ate or touched before they happened, whether they happen every time, and how bad they are.

They might also suggest skin testing if you’re eligible. Or they might recommend an oral food challenge - where you eat small amounts of the suspected food under medical supervision. This is the gold standard for confirming a food allergy.

And remember: allergies can change. A child who tests positive for milk at age 2 might outgrow it by age 5. A teenager with a moderate peanut IgE might need retesting every few years. Allergy isn’t static. Your body changes. So should your testing plan.

Final Thought: Don’t Let a Number Dictate Your Life

Specific IgE testing is powerful. But it’s not magic. A number on a page can’t tell you how you’ll feel. Only your body can. That’s why clinical history matters more than the test result. If you’ve eaten peanut butter for 10 years without a problem, and your IgE is 0.8 kUA/L - you’re probably fine. Don’t panic. Don’t avoid food because of a number. Work with a specialist. Ask questions. Understand the context.

Because allergies aren’t about numbers. They’re about your life. And your life should be guided by real experience - not just a lab report.

Can specific IgE testing diagnose all types of allergies?

No. Specific IgE testing only detects IgE-mediated allergies - the ones that cause immediate reactions like hives, swelling, asthma, or anaphylaxis. It won’t find non-IgE allergies, such as food intolerances (like lactose intolerance), delayed reactions (like eczema flares from dairy), or autoimmune conditions. If your symptoms are vague or delayed, other tests or elimination diets may be needed.

Is specific IgE testing more accurate than skin testing?

Not necessarily. Skin prick testing is generally more sensitive - it detects about 15-20% more true allergies than blood tests for common aeroallergens. But blood tests are more convenient and safer in certain cases: if you’re on antihistamines, have severe eczema, or have a history of severe reactions. Neither test is perfect. Both should be interpreted with your medical history.

What does a low positive result (0.35-0.70 kUA/L) mean?

It means your immune system has detected the allergen, but it doesn’t confirm a clinical allergy. Many people with low levels have never had symptoms. Always check your total IgE level - if it’s high (e.g., over 100 kUA/L), a low specific IgE might be insignificant. Your doctor may recommend observation, retesting, or an oral food challenge instead of avoidance.

Can I get false positives from specific IgE testing?

Yes. False positives are common when testing too many allergens at once. Panels with 20+ tests can produce false positives in up to 60% of cases due to statistical chance. Cross-reactivity also causes false positives - like reacting to birch pollen and testing positive for apples. Always test based on your history, not a broad panel.

Do I need to stop my medications before the test?

No. Unlike skin testing, specific IgE blood testing is not affected by antihistamines, asthma inhalers, or most other medications. You can continue your regular meds. This is one of its biggest advantages - especially for people who rely on daily allergy or asthma drugs.

How often should I repeat the test?

There’s no fixed schedule. For children, retesting every 1-2 years can show if they’ve outgrown an allergy. For adults, repeat testing is usually only needed if symptoms change, a new food is introduced, or before starting immunotherapy. Most people don’t need to repeat it unless there’s a clear clinical reason.

Can specific IgE testing predict how bad my reaction will be?

Sometimes, but not always. Higher IgE levels (e.g., over 15 kUA/L for peanut) strongly correlate with risk of anaphylaxis. But some people with low levels still have severe reactions, and others with high levels never react. It’s a guide - not a crystal ball. Clinical history and component-resolved diagnostics give better insight than IgE levels alone.

Is component-resolved diagnostics worth it?

It can be, especially for nut, seed, or pollen-related allergies where cross-reactivity is common. For example, distinguishing between a true cashew allergy and a birch pollen cross-reaction can prevent unnecessary food avoidance. But it’s expensive and requires expert interpretation. It’s not needed for everyone - just for complex cases.

Natanya Green

February 21, 2026 AT 11:46OMG I JUST FOUND OUT I’M ALLERGIC TO BIRCH POLLEN??? AND THAT’S WHY I GET ITCHY MOUTH FROM APPLES??!?!?!?!?!

I’ve been eating apples since I was 3, no problem. Then last spring? Suddenly my tongue felt like it was being tickled by a demon. I thought I was dying. Went to the allergist, they did the test, and BAM-18 kUA/L for birch. Now I know. I’m not crazy. It’s science. Also, I’m never eating apples again. RIP Granny Smith.

Also?? I stopped taking antihistamines for 3 days to get skin tested? That was a nightmare. My face looked like a pimple battlefield. Blood test? Please. Give me the needle and the quiet.

Also also?? I’m now obsessed with CRD. I want a full 112-component chip. I’m basically a walking allergy lab now. Send help. Or more test tubes.

Steven Pam

February 23, 2026 AT 10:16This is actually one of the clearest explanations of IgE testing I’ve ever read. Seriously, kudos to the author.

I used to think allergy testing was just a shot in the dark-‘Try avoiding dairy, maybe gluten, oh and also cats.’ Now I get it: it’s about matching symptoms to specific triggers. No more guessing games.

My kid had eczema so bad, skin tests were impossible. Blood test found a moderate peanut reaction. We avoided it. No more rashes. No more panic. Just peace. And yes, I cried when the results came back. Not from fear-from relief.

Don’t let numbers scare you. Let them guide you. And always, always talk to an allergist. Not Google. Not Reddit. A real human who’s seen 10,000 cases.

Timothy Haroutunian

February 24, 2026 AT 06:37Let me just say this: the entire premise of this article is built on a fundamental misunderstanding of immunology. Specific IgE testing is not a diagnostic tool-it’s a statistical proxy with a 30% false positive rate across the board. The fact that labs still bill this as ‘gold standard’ is a scandal.

Component-resolved diagnostics? Sounds fancy. But it’s just expensive marketing wrapped in jargon. Most allergists don’t even use it. And when they do? They’re usually just confirming what they already knew from history.

Also, ‘don’t test without a reason’? Tell that to the 2000 people who got tested because their cousin had an anaphylaxis scare. Or because they saw a TikTok video. This whole system is a money machine. And you’re all just paying for it.

Stop trusting labs. Trust your body. If you’ve eaten it for 15 years? You’re fine. End of story.

Erin Pinheiro

February 24, 2026 AT 16:08Wait so if your total IgE is high then a low specific IgE means nothing??

That’s wild. I had a test last year and got a 0.6 for milk. I’ve never had a problem. But my total IgE was 140. So… I’m basically allergic to nothing? Or everything? I’m confused.

Also I think they should test for 500 things not 20. Like… what if I’m allergic to glitter? Or Wi-Fi? I’ve been sneezing since I got my smart fridge.

Also why is everyone so obsessed with peanuts? I’m more scared of soy sauce. Nobody tests for soy sauce. That’s discrimination.

Michael FItzpatrick

February 25, 2026 AT 11:14What I love about this piece is how it doesn’t just throw numbers at you-it gives you context. A number isn’t a verdict. It’s a whisper from your immune system.

I used to think allergies were binary: you’re allergic or you’re not. Turns out, it’s a gradient. A spectrum. Like love. Or grief. Or how much coffee you can handle before your heart starts drumming.

My sister had a 0.4 kUA/L for egg. She’d eaten them since infancy. We didn’t avoid them. We watched. We listened. No reaction. Zero. That’s the power of combining history with science.

And CRD? That’s the future. Not because it’s flashy. But because it cuts through the noise. It tells you: this protein triggers anaphylaxis. That one? Just gives you a tingly lip. That’s life-changing.

Don’t fear the test. Embrace the conversation it starts.

Larry Zerpa

February 25, 2026 AT 14:43Everyone here is acting like this test is sacred. It’s not. It’s a commercial product. The labs make money off every panel you buy. Every false positive leads to unnecessary avoidance. Every unnecessary avoidance leads to anxiety. Every anxiety leads to more testing.

The ‘gold standard’? That’s a lie. Skin testing is more sensitive. Period. Blood tests are for people who can’t handle needles or are on meds. Not because they’re better.

And component-resolved diagnostics? That’s not innovation. That’s corporate greed. You’re paying $800 to find out you’re not allergic to cashew-because you’re allergic to birch. And then you’re told to ‘see a specialist.’ Who charges $400/hour.

This isn’t medicine. It’s a pyramid scheme with lab coats.

Gwen Vincent

February 26, 2026 AT 01:21I just want to say thank you for writing this. I’ve been scared of my own allergies for years. I thought if the test said ‘positive’ I had to live in fear forever.

But reading this made me realize: it’s not about the number. It’s about what happens when I eat it. Do I break out? Do I feel dizzy? Do I need an EpiPen?

I had a 3.2 for shrimp. I’ve eaten it since I was 8. No reaction. So I didn’t avoid it. I just stayed calm. And now I’m eating shrimp tacos every Friday. No drama.

Science is a tool. Not a judge. I’m so glad I read this before I made a life decision based on a lab report.

Christopher Brown

February 28, 2026 AT 00:52USA is too soft. We test for everything. In Germany, they only test if you’ve had a reaction. No panels. No nonsense. Just history. No one tests for ‘gluten’ if you’ve never had diarrhea after bread.

Here? Everyone’s allergic to everything. Because we’re scared. Because we’re lazy. Because we’d rather avoid than adapt.

Test for peanuts? Fine. Test for birch? Fine. Test for glitter? No. You’re not allergic to your iPhone. Stop it.

Lou Suito

February 28, 2026 AT 01:39Why is no one talking about how the lab reports are misleading? They say ‘positive’ like it’s a diagnosis. But 0.35 is the cutoff. That’s like saying ‘you’re pregnant if you have one HCG unit.’ No. You need more.

Also I saw someone say ‘don’t test if you’ve eaten it before.’ What if you ate it once at a party 10 years ago and got a rash? That counts. It’s not ‘documented tolerance’ if you don’t remember.

And CRD? I don’t care if it’s expensive. I want it. I want to know which protein is the villain. I’m not a child. I want details.

Joseph Cantu

February 28, 2026 AT 07:09They’re hiding something. Why do they only test for 20 allergens? What about the 500 others? What about mold in your basement? What about the new 5G tower? What about the fluoride in your water? They don’t test for those because the corporations don’t profit from it.

My cousin’s neighbor had a reaction after using a new laundry detergent. They tested for peanuts, milk, soy. Nothing. But the detergent? They didn’t test for it. Why? Because it’s not profitable.

I think this whole system is designed to keep us dependent. We’re not being told the truth. We’re being sold fear.

And don’t get me started on ‘oral food challenge.’ That’s just a controlled exposure. They’re testing on us. And we’re paying for it.

William James

March 1, 2026 AT 17:42There’s a deeper truth here: we’ve outsourced our bodies to machines. We let a machine tell us what our body feels. But the body doesn’t lie. The number does.

I think we’re afraid of uncertainty. So we demand a number. A grade. A label. But allergies aren’t math. They’re biology. And biology is messy.

My daughter tested positive for milk at 1. We avoided it. At 3, she ate yogurt. No problem. At 5, she had ice cream. No problem. The test was wrong. Or maybe it was just a phase.

Maybe the real allergy is our fear of not knowing. Maybe healing isn’t in the lab. Maybe it’s in the quiet, patient listening-to our bodies, not our reports.

Let the numbers guide. But don’t let them rule.

David McKie

March 2, 2026 AT 09:54Let’s be honest: the whole IgE testing industry is a British invention that the Americans have turned into a carnival. We had it right in the UK-test when symptoms are clear. Not before. Not because of fear. Not because of a viral post.

And now we have this ‘component-resolved’ nonsense? Sounds like something a pharmaceutical exec dreamed up after a three-martini lunch.

I’ve seen patients avoid entire food groups because of a 0.7 reading. They’re malnourished. They’re anxious. They’re terrified. All because a machine said ‘yes.’

Stop testing. Start listening.

Timothy Haroutunian

March 2, 2026 AT 12:22And now I see why people keep saying ‘don’t test without reason.’ I just read a comment from someone who got tested because their dog sneezed near a peanut butter jar. That’s not a reason. That’s a meme.

Testing is not entertainment. It’s medicine. If you’re not going to change your behavior based on the result? Then don’t test.

It’s that simple.