Ulcers: What They Feel Like and How to Handle Them

Ulcers—usually peptic ulcers—are open sores that form on the lining of your stomach or the first part of your small intestine. Most people notice a burning or gnawing pain in the upper belly, often between meals or at night. That pain can wake you up or get better after eating; either way, it’s a sign you shouldn’t ignore.

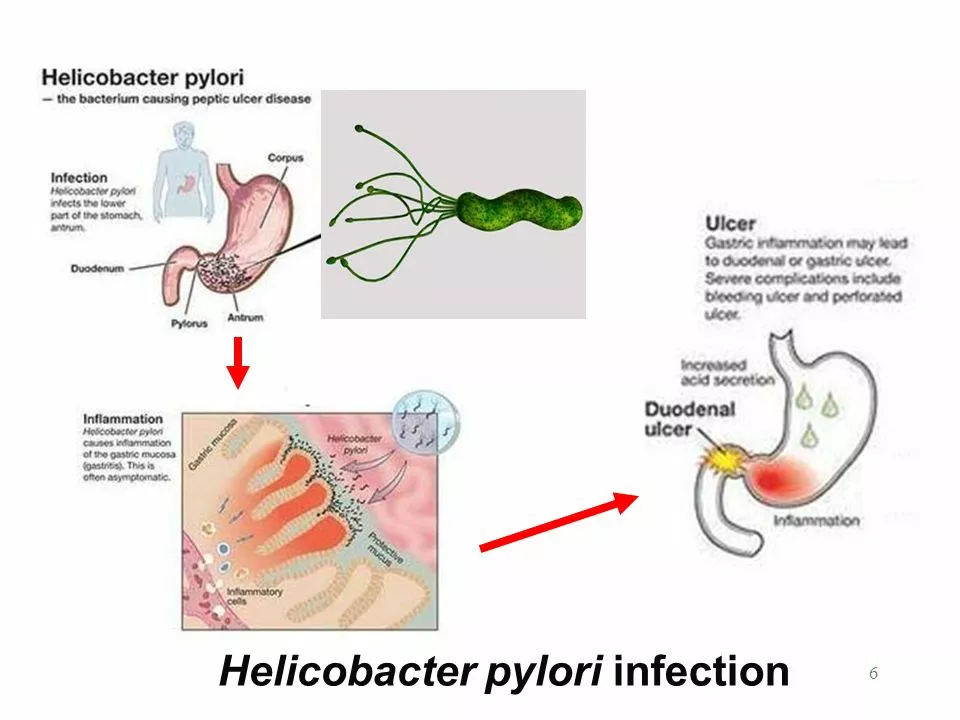

Two main causes explain most ulcers: an infection with Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) or long-term use of NSAID painkillers like ibuprofen and naproxen. Smoking and heavy alcohol use increase the risk, and so does chronic stress when it changes your habits (poor sleep, more smoking, worse diet). Ulcers are common, but they can get serious if they bleed or perforate.

Symptoms & When to See a Doctor

Early signs are easy to miss: dull burning in the upper stomach, belching, mild nausea, or loss of appetite. Seek medical help right away if you see any of these red flags: sharp, sudden stomach pain; black or tarry stools; vomiting blood; or fainting/lightheadedness. Those can mean bleeding or a hole in the stomach and need emergency care.

If your pain keeps returning or lasts for more than a week, book a doctor visit. They’ll ask about NSAID use, test for H. pylori (breath, blood, stool, or biopsy), and may recommend an endoscopy if symptoms are severe or don’t respond to initial treatment.

Treatment and Practical Steps That Work

For H. pylori infections, doctors usually prescribe a short antibiotic course plus a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) to lower stomach acid. If NSAIDs caused the ulcer, stopping or switching painkillers is the first step and a PPI often speeds healing. H2 blockers and antacids can help mild symptoms but don’t replace medical treatment when an infection or serious ulcer is present.

Little changes you can do now: stop smoking, cut back on alcohol, and avoid long NSAID use unless your doctor says it’s okay. Eat regular meals and note which foods trigger your symptoms—coffee, very spicy food, and high-fat meals can worsen pain in some people. Stay hydrated and keep a symptom diary to share with your clinician.

Follow-up matters. After treatment for H. pylori, doctors often repeat testing to confirm the infection is gone. If symptoms return, ask about further evaluation. Untreated ulcers can bleed, cause anemia, or lead to more serious complications that need surgery.

Simple prevention: use acetaminophen instead of NSAIDs when possible, get tested for H. pylori if you have a family history or recurring symptoms, and keep alcohol and smoking in check. If you have chronic pain requiring NSAIDs, ask your provider about protective strategies like co-prescribing a PPI.

If you’re unsure whether your belly pain is an ulcer or something else—acid reflux, gallbladder issues, or gastritis—talk to a healthcare pro. Quick testing and the right treatment usually fix ulcers and get you back to normal fast.