QT Prolongation Risk Calculator

Input Parameters

Risk Assessment Results

Enter your information above to see your risk assessment

When you're prescribed an antidepressant, you're usually focused on how it will help your mood, sleep, or anxiety. But there’s a quiet, hidden risk with two of the most common SSRIs: citalopram and escitalopram. Both can stretch out the QT interval on your ECG - a change that, in rare cases, can trigger dangerous heart rhythms. This isn’t theoretical. It’s why regulators around the world changed the rules in 2011, and why your doctor now checks your dose, age, and heart history before prescribing them.

What’s the real difference between citalopram and escitalopram?

Citalopram is a mix of two mirror-image molecules - the R and S forms. Escitalopram is just the S form, the one that actually works to boost serotonin. That’s why escitalopram works at half the dose: 10 mg of escitalopram is roughly as strong as 20 mg of citalopram. But here’s the catch - the R form in citalopram doesn’t just sit there. It contributes to QT prolongation. That’s why citalopram pushes the QT interval further than escitalopram at the same dose.

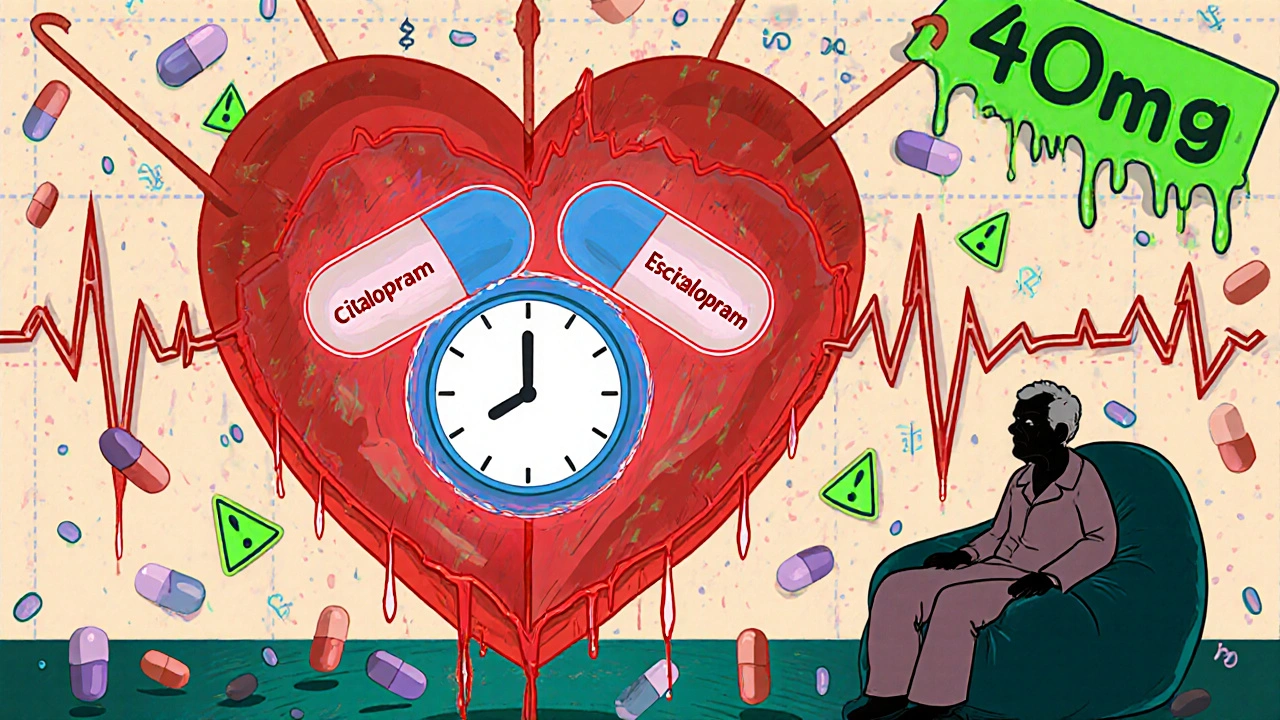

At 20 mg daily, citalopram lengthens the QT interval by about 8.5 milliseconds. At 40 mg, that jumps to 12.6 ms. At 60 mg - a dose once commonly used - it spikes to 18.5 ms. Escitalopram? At 10 mg, it’s only 4.5 ms. At 20 mg, it’s 6.6 ms. Even at 30 mg, it’s still under 11 ms. That difference isn’t just statistical. It’s clinical.

Why does QT prolongation matter?

Your heart has an electrical cycle. The QT interval measures how long it takes for the lower chambers to recharge after each beat. If it’s too long, your heart can misfire. The worst-case scenario is Torsade de Pointes - a chaotic, life-threatening rhythm that can turn into ventricular fibrillation and stop your heart. It’s rare, but it happens. And it’s more likely if you’re older, have low potassium or magnesium, take other QT-prolonging drugs, or have a history of heart disease.

The red flag isn’t just the number on the ECG. It’s when the QTc (corrected for heart rate) hits 500 milliseconds or more. Or if it increases by 60 ms or more from your baseline. That’s the threshold regulators use to say: stop here. Even if you feel fine, your heart might be on shaky ground.

What do the regulators say - and why does it vary?

In 2011, the U.S. FDA warned that citalopram doses above 40 mg daily could be dangerous. They didn’t mention escitalopram as strongly at first. But in the UK, the MHRA looked at the same data and said: both drugs carry risk. So they capped escitalopram at 20 mg daily for adults, and 10 mg for people over 65. Canada followed the FDA. New Zealand’s Medsafe aligned with the UK.

Why the difference? It came down to how each agency weighed the evidence. The FDA focused on the bigger QT effect from citalopram. The UK took a more cautious route - if both drugs do it, even a little, and we can’t predict who’s at risk, then lower the ceiling for both. It’s a precautionary approach. In New Zealand, where aging populations are growing, that caution made sense.

Dose limits today - what’s actually safe?

Here’s what’s recommended right now, based on global guidelines:

- Citalopram: Max 20 mg daily for patients over 65. Max 40 mg daily for adults under 65. Never go above 40 mg, even if you feel it’s not working. Higher doses don’t help depression more - they just raise heart risk.

- Escitalopram: Max 10 mg daily for patients over 65. Max 20 mg daily for adults under 65. Some clinicians will start at 5 mg in elderly patients or those with liver issues.

These aren’t arbitrary numbers. They’re based on real data from clinical trials and post-marketing reports. A 2013 study in the PMC found that while both drugs carry risk, citalopram’s higher doses pushed more people over the 500 ms threshold. Escitalopram, even at 20 mg, rarely did.

Who’s most at risk?

It’s not just about the dose. Your body matters too:

- Age 65+: Your liver and kidneys clear these drugs slower. That means higher blood levels, even at standard doses.

- Heart disease history: If you’ve had a heart attack, heart failure, or abnormal rhythms, avoid these drugs unless closely monitored.

- Low potassium or magnesium: These electrolytes keep your heart’s rhythm steady. Diuretics, vomiting, or poor diet can drop them.

- Other QT-prolonging drugs: Antibiotics like azithromycin, antifungals like fluconazole, anti-nausea meds like ondansetron, or even some antipsychotics can stack the risk.

- Genetic risk: Some people have inherited long QT syndrome - often undiagnosed. If you’ve had fainting spells or sudden cardiac death in your family, tell your doctor.

One study found that patients on citalopram with two or more of these risk factors had a 3.5 times higher chance of developing dangerous arrhythmias. That’s not a small number.

How do other antidepressants compare?

Not all SSRIs are the same. Fluoxetine, sertraline, and paroxetine have minimal effect on the QT interval. Even the SNRI venlafaxine is low risk at standard doses - though overdose can be dangerous.

Tricyclic antidepressants like amitriptyline and maprotiline? They’re worse than citalopram. They’re more likely to cause arrhythmias, especially in overdose. That’s why they’re rarely first-line anymore.

If you have heart concerns, escitalopram is often the preferred SSRI - not because it’s risk-free, but because its risk profile is better. And if you’re already on citalopram at 40 mg? Your doctor should consider switching you to escitalopram at 20 mg. You’ll get the same antidepressant effect with less cardiac strain.

What about long-term use?

Many people take these drugs for years. Does the risk build up? The data says no - the QT effect happens quickly, within days. It doesn’t get worse over time. But that also means if you start a new drug, or change your dose, or get sick and lose electrolytes - you’re back at risk.

Regular ECGs aren’t needed for everyone. But if you’re over 65, on a higher dose, or have any of the risk factors above, your doctor should check your QT interval before starting and again after 2-4 weeks. That’s standard practice now.

What if I’m already on one of these drugs?

Don’t stop suddenly. Depression can worsen, and withdrawal can cause its own problems. But do this:

- Check your current dose. Is it above the limits?

- Ask your doctor if you have any heart risk factors you didn’t know about.

- Ask if an ECG is needed - especially if you’ve had dizziness, palpitations, or fainting.

- If you’re on citalopram at 40 mg or higher, ask about switching to escitalopram at 20 mg.

Most people tolerate these drugs just fine. The risk of serious arrhythmia is low - less than 1 in 1,000. But when it happens, it’s often sudden. That’s why we manage the risk before it becomes an emergency.

Bottom line: Safer prescribing is possible

Citalopram and escitalopram are effective. But they’re not risk-free. The key isn’t avoiding them - it’s using them wisely. Dose limits exist for a reason. Age, heart health, and other medications matter. Escitalopram is often the smarter choice, especially for older adults or those with any cardiac history.

If you’re on one of these drugs, talk to your doctor. Ask: Is my dose safe? Do I need an ECG? Is there a better option? You deserve to feel better - without putting your heart at risk.

Can citalopram or escitalopram cause sudden cardiac death?

Yes, but it’s extremely rare. The risk comes from QT prolongation leading to Torsade de Pointes, a dangerous heart rhythm that can turn fatal. This mostly happens at high doses (above 40 mg for citalopram) or in people with multiple risk factors like older age, low electrolytes, or existing heart disease. For most healthy people on recommended doses, the risk is very low.

Is escitalopram safer than citalopram for the heart?

Yes. Escitalopram causes less QT prolongation at equivalent antidepressant doses. At 20 mg, escitalopram increases the QT interval by about 6.6 ms, while citalopram at 40 mg increases it by 12.6 ms. For patients with heart risk factors, escitalopram is generally preferred because it offers similar depression relief with lower cardiac risk.

Why is the max dose for citalopram lower in people over 65?

As we age, our liver and kidneys process medications more slowly. This means citalopram builds up in the bloodstream at standard doses, increasing QT prolongation risk. The 20 mg daily limit for older adults reduces blood levels and lowers the chance of dangerous heart rhythms. This isn’t about effectiveness - it’s about safety.

Can I take citalopram or escitalopram if I have a pacemaker?

Having a pacemaker doesn’t automatically rule out these medications, but it does require caution. Pacemakers can’t prevent Torsade de Pointes - they only pace the heart if it beats too slowly. If your QT interval is prolonged, you’re still at risk for dangerous rhythms. Your doctor will likely check your ECG and may prefer escitalopram at a lower dose, especially if you have other risk factors.

Do I need an ECG before starting citalopram or escitalopram?

Not always - but it’s strongly recommended if you’re over 65, have heart disease, take other QT-prolonging drugs, or have symptoms like dizziness or fainting. Many clinics now do a baseline ECG before starting these medications in high-risk patients. It’s a simple, non-invasive test that can prevent serious complications.

What if I miss my ECG and I’m on a high dose?

If you’re on citalopram above 40 mg or escitalopram above 20 mg and haven’t had an ECG, contact your doctor immediately. Don’t wait for symptoms. Your doctor may recommend lowering your dose and scheduling an ECG. Most people who’ve taken higher doses without monitoring haven’t had problems - but the risk is real enough that guidelines now require it.

Are there any natural supplements I should avoid with these drugs?

Yes. St. John’s Wort can increase serotonin levels and may raise the risk of serotonin syndrome. Also, avoid high-dose magnesium or potassium supplements unless prescribed - too much can affect heart rhythm, and too little (from poor diet or diuretics) increases QT risk. Always tell your doctor about any supplements you take.

Neoma Geoghegan

November 23, 2025 AT 13:28QT prolongation is no joke. I’ve seen patients drop on the floor from Torsade with no warning. Citalopram at 60mg? That’s playing Russian roulette with a pacemaker.

Bartholemy Tuite

November 25, 2025 AT 00:06bro i was on 40mg citalopram for 3 years and felt fine until i got sick and my potassium dropped. ended up in the er with a 512ms QT. doc switched me to escitalopram 10mg and i’m still here. dont be that guy who thinks ‘i feel fine so its fine’ - your heart dont text back.

Sam Jepsen

November 26, 2025 AT 22:20As a Canadian clinician, I’ve been pushing escitalopram over citalopram for years. The data’s clear. Lower QT risk, same efficacy. Plus, patients tolerate it better. Why risk the 12ms spike when you can get the same mood lift with 6.6ms? Simple math.

Yvonne Franklin

November 26, 2025 AT 22:51ECG before starting these drugs should be standard not optional. Especially if you’re over 50 or on diuretics. One test saves lives. Period.

james lucas

November 28, 2025 AT 12:39man i just found out my grandma was on citalopram 40mg and she’s 72. she’s had dizziness for months but thought it was just aging. i’m gonna call her doc right now. thanks for this post - real life saver stuff.

Jessica Correa

November 28, 2025 AT 23:48St John’s Wort is a sneaky one. I took it with escitalopram for ‘natural anxiety relief’ and ended up with serotonin syndrome. Not fun. Always tell your doc about supplements. Even the ‘harmless’ ones.

manish chaturvedi

November 29, 2025 AT 17:05In India, many patients self-medicate with SSRIs bought over the counter. The awareness gap is massive. This information must be translated and circulated in local languages. A simple ECG could prevent cardiac arrests in elderly patients who never knew they were at risk.

Michael Fitzpatrick

November 30, 2025 AT 01:32People act like QT prolongation is some rare glitch but it’s actually more common than you think - especially when you stack risk factors. I had a patient on citalopram 40mg, on fluconazole, with low Mg, and over 70. She didn’t even know she had a heart condition. Got an ECG, QT was 508ms. Switched to sertraline. She’s been fine for 2 years now. Prevention beats crisis every time.

Shawn Daughhetee

November 30, 2025 AT 18:20my doc never mentioned QT at all when prescribing my 20mg escitalopram. i’ve been on it for 4 years. no issues. but now i’m paranoid. should i get an ECG? i’m 58, have mild hypertension, take a little lasix. maybe i’m overthinking it but i’d rather be safe than sorry.

Miruna Alexandru

November 30, 2025 AT 19:46It’s fascinating how regulatory agencies cherry-pick data to suit their institutional biases. The FDA focused on citalopram’s R-enantiomer while the MHRA treated both drugs as equally risky - but the pharmacokinetic data doesn’t justify such divergent limits. Escitalopram’s 20mg cap is arbitrary when its QT effect is demonstrably lower. This isn’t science - it’s risk aversion dressed as policy.

Justin Daniel

December 2, 2025 AT 06:00so you’re telling me i can swap my 40mg citalopram for 20mg escitalopram and get the same mood boost but with less chance of my heart throwing a tantrum? and you wonder why i still trust doctors…

Julie Pulvino

December 3, 2025 AT 19:25My mom switched from citalopram to escitalopram last year. She’s 71, had a tiny stroke in 2018. Doc said ‘this is the safer path.’ She’s been sleeping better, less anxiety, no dizziness. No ECG needed because she’s low-risk otherwise. But the fact that we even talked about it? That’s the win. Knowledge saves lives.