By 2025, generic drugs made up over 90% of all prescriptions filled in the United States - yet they accounted for just 23% of total drug spending. That’s not magic. It’s policy. Across the world, governments are using different tools to make medicines cheaper, faster, and more accessible. But not all approaches work the same. Some slash prices so hard that manufacturers quit. Others create confusion by letting the same pill cost three times more just across the border. What works in South Korea might fail in India. What saves money in Germany might cause shortages in China. Understanding how different countries handle generics isn’t just about economics - it’s about who gets treated and who doesn’t.

How the U.S. Got to 90% Generic Use - And Why It Still Pays More

The U.S. doesn’t lead the world in drug prices by accident. It leads because of how it handles generics. The FDA’s Orange Book lists over 11,000 approved generic drugs as of late 2024. The system is built on the Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984, which let companies skip expensive clinical trials if they proved their version worked the same as the brand-name drug. That’s called bioequivalence - meaning the generic delivers the same amount of medicine into the bloodstream within a narrow range (80-125% of the original). That’s why 90.1% of U.S. prescriptions are filled with generics. But here’s the twist: even with that level of use, Americans still pay more for drugs than people in Canada, Germany, or the UK. Why? Because the branded drugs - the ones still under patent - are priced sky-high. The savings from generics don’t cancel out the cost of the rest. Medicare saved $142 billion in 2024 from generics alone - $2,643 per beneficiary. But that’s not enough to fix the system. The real issue isn’t the generic market. It’s the lack of price controls on brand-name drugs. The FDA also created a special fast-track called Competitive Generic Therapy (CGT). If a drug has little or no competition, companies can get 180 days of exclusive market time. Zenara Pharma used this in August 2025 to launch a generic version of sertraline, a common antidepressant. Their approval came in under 10 months - half the usual time. That’s how the U.S. keeps the pipeline full. But it’s not perfect. Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs) sometimes make patients pay more for generics than for brand names. Reddit users in June 2025 reported that 63% of people were confused or angry about this. It’s not about the drug. It’s about the middlemen.Europe: Harmonized Rules, Fragmented Prices

The European Union has one of the most complex systems in the world. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) approves generics for the whole bloc. That sounds efficient. But then, each country sets its own price. That’s where things break down. A pill made in Germany, approved by the EMA, and sold in France might cost 300% more than the same pill sold in Poland. The OECD found this in 2025. Why? Because some countries use external reference pricing - comparing prices to other nations. The Netherlands, for example, looks at prices in France, Belgium, the UK, and even Norway. Then they set their own price lower than all of them. It’s smart. It’s also unfair. Manufacturers can’t compete across borders because the rules change at every checkpoint. Germany leads in generic use - 88.3% of prescriptions by volume - thanks to mandatory substitution laws. Pharmacists can switch a brand to a generic unless the doctor says no. Italy, with similar income levels, only hits 67.4%. The difference? Culture, training, and trust. A 2025 European Patients’ Forum survey found that 82% of patients were fine with generics - if their pharmacist explained why the switch was safe. But 44% still worried about quality, especially for drugs like blood thinners or epilepsy meds where tiny differences matter. The EU is trying to fix this. Its new Pharmaceutical Package, expected in late 2025, will push for better pricing coordination and faster approval for the first generic to enter the market. But it’s a slow process. For now, Europe’s strength is regulation. Its weakness? Inconsistency.China’s Billion-Dollar Bet: Buy in Bulk, Slash Prices

China’s Volume-Based Procurement (VBP) policy is the most aggressive price-cutting experiment in modern history. Started as a pilot in 2018, it became national by 2020. Instead of letting hospitals negotiate individually, the government collects demand from thousands of hospitals and holds one big auction. The lowest bidder wins - and gets to supply 80% of the country’s need. The results? Average price drops of 54.7%. In some cases, like certain heart medications, prices fell by 93%. Amlodipine, a common blood pressure drug, dropped from $1.20 per pill to $0.08. That’s life-changing for millions. But it’s also risky. By 2025, 23% of manufacturers surveyed by the China Generic Pharmaceutical Association said they were selling VBP drugs at a loss. Some stopped making them. In 2024, 12 provinces ran out of amlodipine for six to eight weeks. Patients on WeChat forums complained. The government didn’t have backups. The system works - until it doesn’t. China’s National Medical Products Administration (NMPA) slashed approval times to 10-12 months. But now, manufacturers face a new problem: no profit margin. The WHO warns that if companies can’t cover costs, they’ll stop producing. Or worse - cut corners. The FDA issued over 2,100 import alerts in 2024 for quality issues from Chinese factories - up from 1,247 in 2020. It’s not that all Chinese generics are bad. It’s that the pressure to win bids is pushing some to risk safety.

India: The World’s Pharmacy - And Its Hidden Costs

India makes 20% of the world’s generic drugs by volume. It’s the go-to source for low-cost medicines for Africa, Latin America, and parts of Asia. That’s thanks to its patent laws. Section 84 of India’s Patents Act lets the government issue compulsory licenses - forcing a company to let others make the drug if it’s too expensive or not available. This is how India made HIV drugs affordable in the early 2000s. It’s how it now supplies generic cancer drugs to 120 countries. But there’s a dark side. In 2022-2024, the FDA issued 17% more warning letters to Indian manufacturers for data integrity issues. Some labs were falsifying bioequivalence tests. One 2025 Lancet report tied this to rising cases of treatment failure in patients taking imported generics for epilepsy and tuberculosis. Indian manufacturers are caught between two worlds. They need to compete on price to win global contracts. But they also need to meet U.S. or EU standards to keep selling there. The Central Drugs Standard Control Organization (CDSCO) cut approval times from 36 months to 14 months by 2025. But state-level price regulators still take 6-9 months to set prices. That delays everything. Physicians on MedIndia Network say 58% of them worry about inconsistent bioavailability - especially for drugs with narrow therapeutic windows. That means the difference between a safe dose and a dangerous one is tiny. If the generic isn’t exactly right, patients can have seizures, strokes, or blood clots. India’s strength is scale. Its weakness is oversight.South Korea: The Tightrope Between Competition and Quality

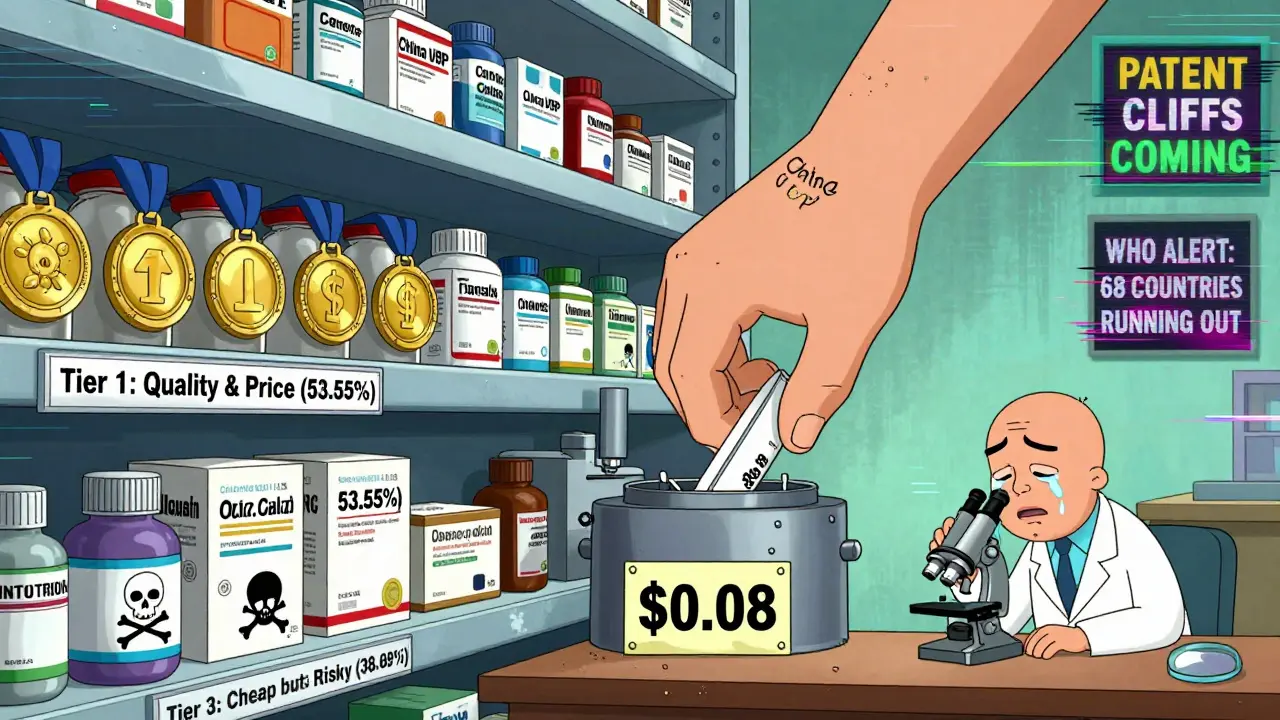

South Korea tried something new in 2020: the ‘1+3 Bioequivalence Policy’. Instead of letting dozens of companies make the same generic, they capped approvals at three. The first company to prove bioequivalence gets approved. Then two more. After that - no more. It worked. Between 2020 and 2024, redundant generic entries dropped by 41%. Fewer companies meant less wasted money on duplicate testing. But it also meant fewer competitors. New generic launches fell by 29% compared to 2015-2019. That slowed price drops. To balance this, they added a ‘Differential Generic Pricing System’. Generics that meet both quality and price standards get set at 53.55% of the brand price. Those meeting only one get 45.52%. The rest? 38.69%. That’s not a discount. It’s a grading system. It forces manufacturers to choose: compete on price, or compete on quality. Most pick quality. But some can’t afford to. Frontiers in Public Health found that this system reduced market chaos - but also reduced innovation. Companies stopped investing in new generics because the payoff was too small. It’s a lesson for other countries: limiting competition can improve quality - but at the cost of long-term affordability.

The Big Risks No One Talks About

The biggest threat to global generic access isn’t patents. It’s manufacturing collapse. As prices fall, margins vanish. The McKinsey 2025 Pharma Outlook predicts the number of global generic manufacturers will drop from 3,500 to 2,200 by 2030. Only the big players with vertical integration - making active ingredients, packaging, and distribution - will survive. The FDA’s import alerts are rising. The WHO warns that 68 countries now use reference pricing. Forty-two have mandatory substitution. But without minimum profit margins (15-20% is recommended), manufacturers can’t maintain quality control. In 2024, the U.S. saw a spike in recalls of generic metformin due to NDMA contamination. It wasn’t fraud. It was cost-cutting on purification. Another hidden risk: patent cliffs. Between 2025 and 2030, $217-236 billion in branded drug sales will expire. That’s a golden opportunity for generics. But if countries don’t fix their approval systems, the market will flood slowly - or not at all. The U.S. takes 18-24 months to approve a generic. Europe adds 6-18 months for pricing. India and China are faster, but unstable. The International Generic and Biosimilars Association says harmonizing global bioequivalence standards could cut approval times by 18-24 months. That’s huge. But no country wants to give up control.What Works - And What Doesn’t

There’s no single model. But some patterns stand out:- High generic use + strong pricing control = savings - U.S. and Germany show this works.

- Aggressive bulk buying = huge price drops but supply risk - China’s model is powerful but fragile.

- Too many generics = market chaos - India and Brazil learned this the hard way.

- Too few generics = no competition = no savings - South Korea’s cap helped quality but hurt affordability.

- Pharmacist education = higher acceptance - Europe’s best results came when patients were informed.

Are generic drugs really as effective as brand-name drugs?

Yes - when they meet regulatory standards. The FDA, EMA, and WHO require generics to deliver the same amount of active ingredient into the bloodstream as the brand-name drug, within a tight range (80-125% for absorption). This is called bioequivalence. Thousands of studies confirm that generics perform the same in real-world use. The main difference is cost - not effect. Some patients report feeling different, but that’s often due to inactive ingredients (like fillers), not the medicine itself.

Why do some countries have cheaper generics than others?

It’s all about policy. Countries like the Netherlands use external reference pricing - they set prices based on what other nations charge. China uses bulk buying to force manufacturers to bid low. The U.S. lets the market compete, but with strong generic adoption. India allows compulsory licensing, letting local firms make patented drugs without permission. Each system has trade-offs: low prices can mean shortages, or lower quality if manufacturers can’t cover costs.

Can generic drugs cause side effects brand names don’t?

Legally approved generics don’t. But poor manufacturing can. In 2024, the FDA issued over 2,100 import alerts for quality issues - mostly from overseas factories. Some generics had impurities, inconsistent dosing, or failed stability tests. These aren’t the norm, but they happen. Drugs for epilepsy, blood thinners, and thyroid conditions are especially sensitive. That’s why regulatory oversight matters more than price.

Why do some insurance plans charge more for generics than brand names?

That’s a flaw in how Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs) design formularies. PBMs get rebates from drugmakers. Sometimes, they structure copays so patients pay more for generics if the brand-name drug gives the PBM a bigger kickback. It’s not about the drug - it’s about profit. Patients in the U.S. report this often. Always check your plan’s formulary or ask your pharmacist. You might be able to switch to a different generic that’s cheaper.

Will generic drugs become less available as prices drop?

Yes - if prices fall below manufacturing cost. China’s VBP system already caused shortages of common drugs like amlodipine in 2024. South Korea’s pricing tiers reduced new generic launches by 29%. Manufacturers need at least a 15-20% gross margin to stay in business. If governments push prices too low, companies shut down production or move out of the market. The result? Fewer choices, and sometimes, no supply at all.

How can I be sure my generic drug is safe?

Check the manufacturer. If you’re in the U.S., look up the drug in the FDA’s Orange Book. If you’re in Europe, check the EMA database. Avoid generics from unknown brands - especially online. Ask your pharmacist if the manufacturer has been flagged by regulators. For critical drugs (like blood thinners or seizure meds), stick with brands or well-known generics. If you notice a change in how you feel after switching, tell your doctor. It’s not always the drug - but it’s worth checking.

Vanessa Barber

January 23, 2026 AT 07:00Everyone acts like generics are this miracle solution, but have you seen the supply chain collapses in China? One month you got your amlodipine, next month your pharmacy says 'out of stock' and your doctor shrugs. It’s not about price-it’s about sustainability. We’re trading short-term savings for long-term risk.

Dawson Taylor

January 24, 2026 AT 09:24The fundamental issue is not regulatory divergence, but the misalignment of incentives. When manufacturers are compelled to operate at negative margins, quality becomes a secondary consideration. The market does not self-correct under such conditions-it fragments.

Laura Rice

January 25, 2026 AT 10:51OMG I just found out my pharmacist gets paid more to push the brand name even when the generic is cheaper?? Like… why?? I’ve been overpaying for years thinking I was being smart. This is insane. Someone needs to fix this PBM mess. #PharmacyScam

Janet King

January 25, 2026 AT 21:34Generic drugs must meet the same bioequivalence standards as brand-name drugs. The active ingredient, dosage, route of administration, and intended effect are identical. Differences in fillers or coatings may cause minor variations in absorption, but these are not clinically significant for most patients.

Stacy Thomes

January 27, 2026 AT 00:38STOP letting corporations decide who gets medicine. China cuts prices so hard people can’t get their heart pills. The U.S. lets PBMs rip us off. India makes the drugs but sometimes they’re sketchy. We need a system that puts PEOPLE first-not profits, not politics. This isn’t rocket science.

Sallie Jane Barnes

January 28, 2026 AT 05:18While it is true that volume-based procurement yields dramatic price reductions, it also introduces systemic fragility. A lack of buffer inventory, coupled with zero-profit bidding, renders the supply chain vulnerable to disruption. This is not an economic strategy-it is a logistical gamble with public health outcomes.

Andrew Smirnykh

January 30, 2026 AT 01:03I lived in India for two years and saw firsthand how generics saved lives-but also how inconsistent quality control created fear. A friend’s epilepsy meds stopped working. Turned out the batch was from a factory that skipped stability tests. It’s not about being anti-India. It’s about demanding better oversight everywhere.

charley lopez

January 31, 2026 AT 18:35The convergence of regulatory fragmentation, margin compression, and supply chain centralization presents a systemic risk profile that exceeds the parameters of traditional pharmaceutical market analysis. The anticipated decline in generic manufacturers to 2,200 entities by 2030 will likely induce oligopolistic pricing dynamics, negating the intended cost-containment objectives of current policy frameworks.