Pharmacies in the U.S. are making more money on generic drugs than on brand-name ones - even though brand drugs cost way more. It sounds backwards, but it’s how the system works. A $5 generic antibiotic might bring a pharmacy $2.50 in profit. A $500 brand-name cancer drug? Maybe $17. That’s not a mistake. It’s the math of the pharmaceutical supply chain, and it’s squeezing independent pharmacies dry.

Why Generics Are the Real Profit Engine

| Drug Type | Share of Prescriptions | Average Gross Margin | Share of Pharmacy Profit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Generic Drugs | 90% | 42.7% | 96% |

| Brand-Name Drugs | 10% | 3.5% | 4% |

Here’s the real story: 9 out of every 10 prescriptions filled are for generics. But those generics make up 96% of a pharmacy’s profit. Why? Because they’re cheap to buy and pharmacies can mark them up by 40% or more. A $1 pill might cost the pharmacy 50 cents. They sell it for $1.25. That’s 150% markup. On a $500 brand drug? The pharmacy might pay $400 and sell it for $415. That’s a 3.75% margin. Volume plus markup equals profit - and generics win on both fronts.

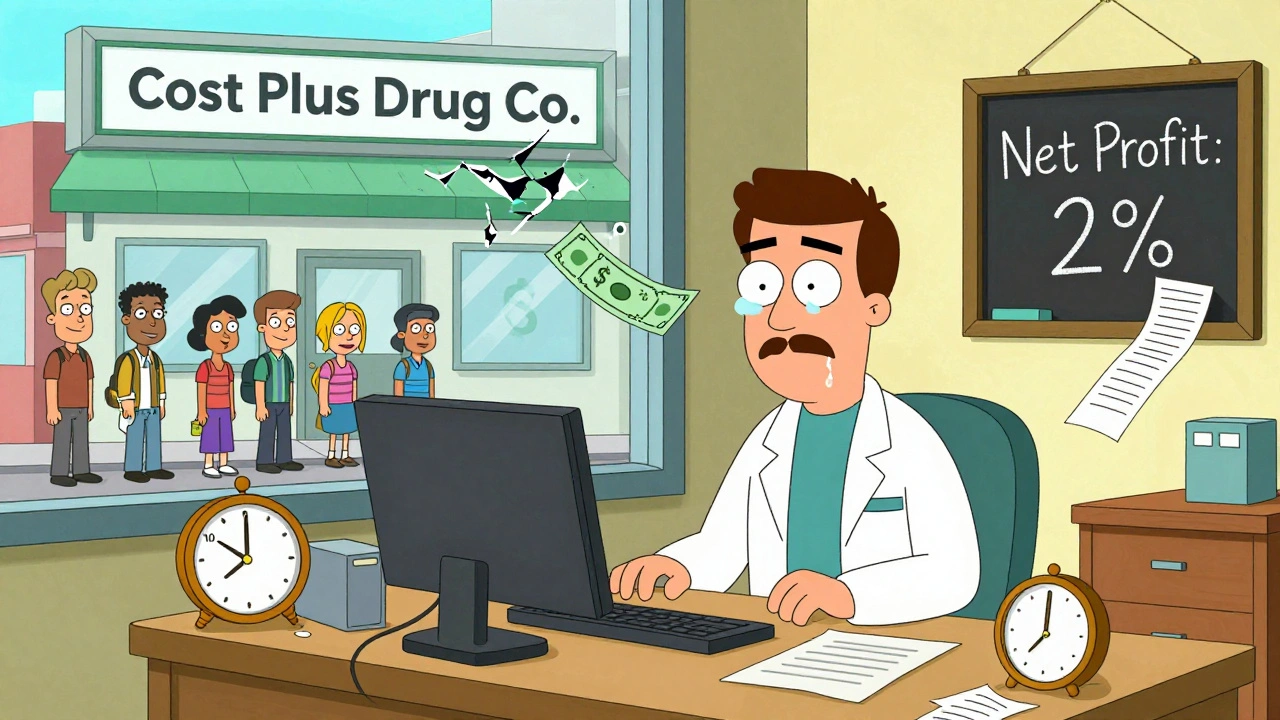

But here’s the catch: that 42.7% gross margin doesn’t mean $42.70 in your pocket. After rent, staff, insurance, utilities, and compliance costs, the net profit on a generic prescription is often just 2% - maybe 25 to 40 cents per script. For many small pharmacies, that’s barely enough to cover the cost of running the register.

Who’s Really Making the Money?

The pharmacy isn’t the only player. The whole system is built on layers of middlemen - manufacturers, wholesalers, pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs), and insurers. PBMs are the biggest hidden force. They negotiate prices with pharmacies and set reimbursement rates. But here’s the trick: they often charge health plans more than they pay the pharmacy. That gap? That’s called spread pricing. The PBM pockets the difference.

For example: A PBM tells a pharmacy to reimburse $3 for a generic drug. The PBM bills the insurer $12. The pharmacy gets $3. The PBM keeps $9. That’s not fraud - it’s legal. But it’s why independent pharmacies are bleeding cash. In 2022, the National Community Pharmacists Association found that 68% of independent pharmacy owners listed declining generic reimbursement as their #1 business threat.

And it’s getting worse. When only one company makes a generic drug - called a single-source generic - competition disappears. Prices spike. In some cases, the single-source generic now costs more than the original brand. SureCost’s 2024 report documented cases where a $20 brand-name drug had a $25 generic version - because no one else could make it. Pharmacies are stuck paying more, but can’t charge patients more without losing business.

The PBM Problem and the Rise of Clawbacks

It’s not just spread pricing. There’s something called clawbacks. A pharmacy dispenses a generic drug and gets reimbursed $5 by the PBM. Later, the PBM says, "Wait - the actual cost of the drug dropped to $3.50. You owe us $1.50." So the pharmacy has to refund money they already spent. This happens after the fact. Sometimes it’s for a drug the patient already took. No warning. No appeal. Just a bill.

Pharmacy Times interviewed an owner in Ohio who said his net profit on generics dropped from 8-10% five years ago to barely 2% now. His rent and payroll went up 35%. He’s not alone. Between 2018 and 2023, over 3,000 independent pharmacies closed. Most didn’t go out of business because they were bad at selling medicine. They went under because the system took their profit and left them with overhead.

How Big Chains Survive - And Why Small Ones Can’t

Big pharmacy chains like CVS and Walgreens don’t operate the same way. Many own their own PBMs. They’re not just retailers - they’re part of the middleman system. They get better reimbursement rates because they’re the ones setting them. They also push patients toward mail-order pharmacies, where margins on generics are up to four times higher than in retail.

Independent pharmacies? They’re stuck in the middle. They can’t negotiate with PBMs. They can’t afford to build their own systems. They’re forced to accept whatever rates are offered - even if it means losing money on every script. Some try to make up for it by selling vitamins, over-the-counter meds, or offering flu shots. But that’s not enough. A flu shot brings in $40. A prescription refill? $0.25 profit.

What’s Changing? New Models Are Emerging

Some pharmacies are fighting back. Mark Cuban’s Cost Plus Drug Company cuts out the middlemen entirely. They charge $20 for a generic drug, plus a $3 dispensing fee. No spreads. No clawbacks. No secrets. They’re processing over a million prescriptions a month. Amazon Pharmacy does something similar - $5 for generics with a clear cost breakdown.

Other pharmacies are shifting to direct contracting. Instead of going through a PBM, they sign contracts directly with employers or unions. They set their own prices. Some are even offering cash-pay options for patients who don’t have insurance. One pharmacy in Texas started offering insulin for $25 cash. No PBM. No mystery. Patients came in droves.

Some are moving into medication therapy management (MTM). Instead of just filling scripts, pharmacists sit down with patients, review all their meds, and catch interactions or duplications. Insurance pays $50-$100 per session. That’s real revenue - not just profit on pills.

The Future: Consolidation or Competition?

The trend is clear: independent pharmacies are shrinking. By 2026, their market share could drop from 40% to 32%. But change is coming. The FTC is investigating PBM practices. States like California and Texas passed laws requiring PBM transparency. The Inflation Reduction Act will let Medicare negotiate drug prices starting in 2026 - which could lower overall drug spending and indirectly ease pressure on pharmacies.

But here’s the real question: Should pharmacies be making 42% gross margins on $1 pills? Or should those savings go to patients? The system was designed to make generics affordable. But now, the profit is going to the middlemen, not the people who need the medicine.

Pharmacies aren’t villains. Most owners are in it because they care. They want to help. But the economics don’t work anymore. Until the reimbursement model changes - until PBMs stop hiding profits in spreads and clawbacks - pharmacies will keep closing. And patients? They’ll pay more, wait longer, and lose access to the people who know their meds best.

What Can Patients Do?

Ask your pharmacist: "What’s the cash price?" Often, it’s cheaper than your copay. Use tools like GoodRx or SingleCare to compare prices. Support local pharmacies that offer transparent pricing. If your pharmacy is struggling, tell your insurer or employer you want them to stop using PBMs that use spread pricing. Change starts with awareness.

Why do pharmacies make more profit on cheap generics than expensive brand drugs?

Because generics are bought at low wholesale prices and sold with high percentage markups. A $1 generic might cost 50 cents to acquire, so selling it for $1.25 gives a 150% markup. A $500 brand drug might cost $400 to buy, so selling it for $415 only gives a 3.75% markup. Volume and markup ratio make generics far more profitable per unit, even if the dollar amount is smaller.

What are clawbacks and how do they hurt pharmacies?

Clawbacks happen when a pharmacy is reimbursed for a generic drug, but later the pharmacy benefit manager (PBM) says the drug’s actual cost dropped. The PBM then demands the pharmacy refund the difference - sometimes after the patient has already taken the medicine. This turns small profits into losses and creates unpredictable cash flow, making it hard for pharmacies to pay bills or staff.

Why are independent pharmacies closing faster than big chains?

Big chains often own their own pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) or have the scale to negotiate better reimbursement rates. Independent pharmacies are at the mercy of PBMs that use spread pricing and clawbacks. They also lack the resources to offer services like medication therapy management or mail-order delivery, which are becoming essential for profitability.

Do generic drug prices always go down when more companies make them?

Usually, yes - but only if there’s real competition. The FDA estimates prices drop about 20% when three or more companies make the same generic. But if only one company produces it - called a single-source generic - prices can skyrocket. Between 2014 and 2016, nearly 100 mergers in the generic industry reduced competition, leading to price spikes on dozens of drugs.

Can pharmacies make more money by selling specialty drugs instead of generics?

Yes - but it’s not easy. Specialty drugs (like those for cancer or rheumatoid arthritis) often come with higher reimbursement rates and require specialized handling. Pharmacies that become certified specialty providers can earn $100-$200 per script. But this requires training, storage systems, and staff expertise. It’s not a quick fix - it’s a business transformation.

What’s the difference between gross margin and net profit for pharmacies?

Gross margin is the profit before expenses - like rent, staff, utilities, and insurance. Net profit is what’s left after all those costs. A pharmacy might have a 42% gross margin on generics, but after paying $2,000 in rent and $4,000 in payroll, their net profit per script might be just 2%. That’s why many pharmacies operate on razor-thin margins - they’re selling volume just to stay afloat.

Final Thought: The System Is Broken - But Not Irreversible

Generics were meant to save money. They did - for patients and insurers. But the profit didn’t go to the people who filled the prescriptions. It went to middlemen. Now, pharmacies are caught in the middle: expected to deliver care, but paid less than the cost of running the store. The solution isn’t to stop generics. It’s to fix how they’re paid for. Transparency. Fair reimbursement. Real competition. Until then, the pharmacy on the corner will keep disappearing - and with it, the human connection that keeps people healthy.

Brian Perry

December 3, 2025 AT 02:14Stacy Natanielle

December 3, 2025 AT 10:50kelly mckeown

December 3, 2025 AT 13:16Tom Costello

December 3, 2025 AT 22:10Wendy Chiridza

December 4, 2025 AT 13:40Palanivelu Sivanathan

December 6, 2025 AT 00:27Adrianna Alfano

December 6, 2025 AT 05:49Casey Lyn Keller

December 8, 2025 AT 03:32Jessica Ainscough

December 9, 2025 AT 19:45May .

December 10, 2025 AT 08:38Sara Larson

December 10, 2025 AT 14:57Kevin Estrada

December 10, 2025 AT 19:14Katey Korzenietz

December 10, 2025 AT 23:38