When you take a medication like warfarin, phenytoin, or lithium, your life depends on it working just right. Not close. Not mostly. NTI drugs - short for Narrow Therapeutic Index drugs - have a razor-thin margin between helping you and harming you. A little too much, and you could bleed internally. A little too little, and you could have a stroke or a seizure. That’s why switching from a brand-name version to a generic version isn’t just a simple cost-saving swap. For these drugs, it’s a gamble with your health.

What Makes a Drug an NTI Drug?

An NTI drug is one where the difference between the dose that works and the dose that poisons you is tiny. The Therapeutic Index is a ratio: the toxic dose divided by the effective dose. If that number is 2 or less, it’s classified as an NTI drug. For example, warfarin has a therapeutic range of 2.0 to 3.0 on the INR scale. Go below 2.0? You’re at risk of a blood clot. Go above 3.0? You could bleed out. There’s no room for error.

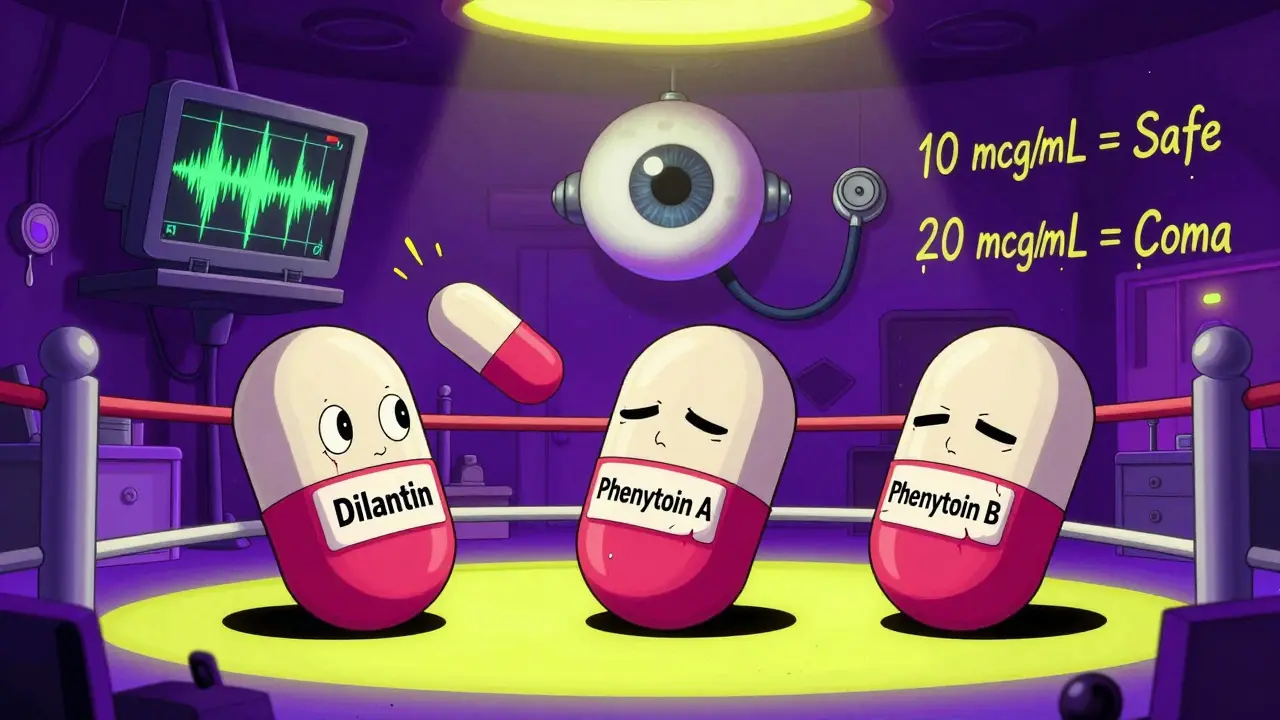

Phenytoin, used for seizures, has a similar tight window. The safe level is between 10 and 20 mcg/mL. Above 20? You get dizziness, blurred vision, even loss of coordination. Below 10? Seizures return. Lithium for bipolar disorder? Same story. Too low, and mood swings return. Too high, and you risk kidney damage, tremors, or coma.

These aren’t rare drugs. About 15 to 20 percent of commonly prescribed medications fall into this category. Others include digoxin, theophylline, and methadone. Each one has a unique way of acting in the body - but all share the same dangerous trait: small changes in blood levels lead to big changes in outcomes.

The Bioequivalence Problem

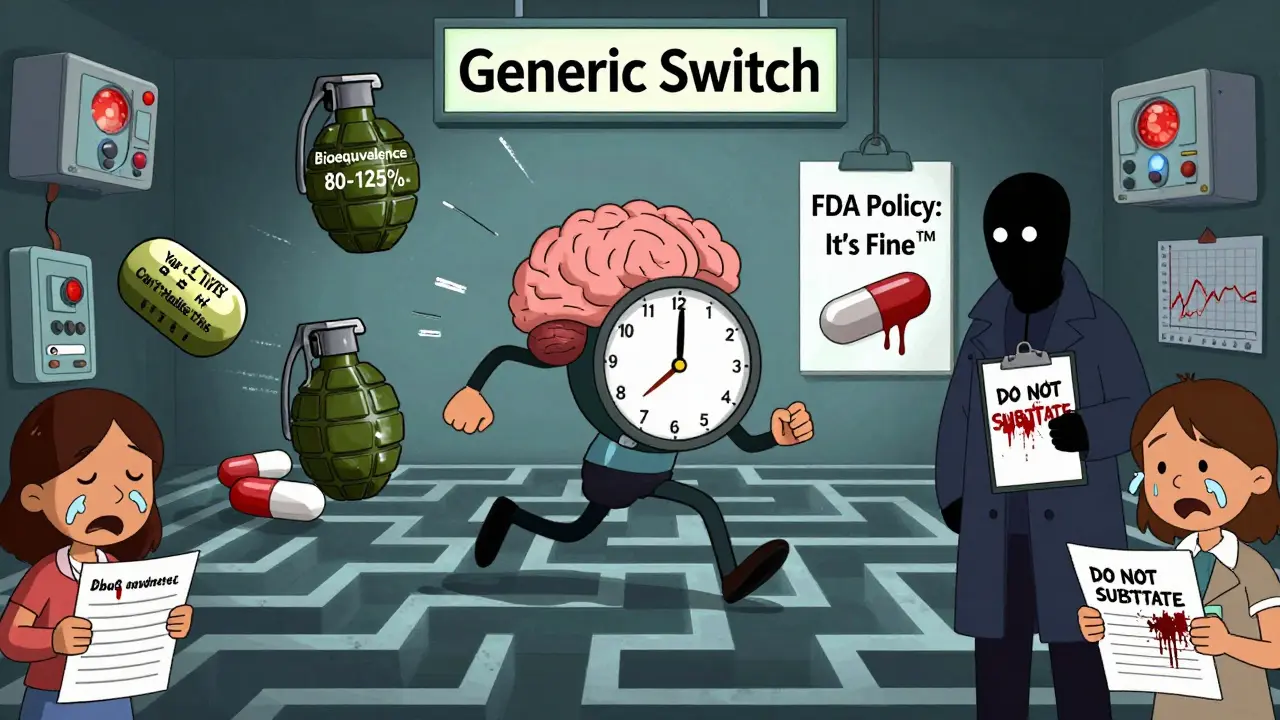

The FDA allows generic drugs to be approved if they’re within 80% to 125% of the brand-name drug’s absorption rate. That sounds precise - until you realize that for an NTI drug, that 45% swing is massive. If the effective dose is 10 units, and the toxic dose is 20, then a 20% variation could push you from 9.5 (safe) to 11.5 (toxic). That’s not a technicality. That’s a life-or-death gap.

For warfarin, studies show mixed results. One 2007 study found no major issues when switching generics. But other studies documented patients slipping out of their target INR range after a switch - even when nothing else changed. One patient might stay stable. Another might end up in the ER with a brain bleed. Why? Because absorption varies. Some generics dissolve slower. Others are absorbed more quickly. For NTI drugs, that difference matters.

Phenytoin has a long history of problems. In the 1980s, multiple patients had breakthrough seizures after switching from brand-name Dilantin to a generic. Their blood levels dropped just enough to lose seizure control. In another case, a patient developed toxicity after switching to a generic with higher bioavailability. The same dose, different result.

Why Doctors and Pharmacists Disagree

The FDA says generics for NTI drugs are therapeutically equivalent. But many clinicians don’t believe it. The American Medical Association has a clear policy: the prescribing physician should decide whether to allow substitution. That’s not a suggestion. It’s a warning.

Pharmacists are caught in the middle. A 2019 survey showed most pharmacists trust generic NTI drugs - but those working outside big pharmacy chains were more skeptical. Female pharmacists were more likely to question the switch. Why? Because they’ve seen the fallout. One pharmacist in rural Wisconsin told a colleague about a patient who started bleeding after switching from brand to generic warfarin. The patient didn’t know the difference. Neither did the pharmacist - until the INR test came back at 6.2.

Some experts go further. They argue that generic substitution shouldn’t even be allowed for NTI drugs. Their logic? If the therapeutic window is that narrow, then any variation in absorption, even within FDA limits, breaks the rule of safety. It’s like saying two cars are the same because they both go 60 mph - even if one has bad brakes.

Real Risks, Real Stories

For patients on opioids like methadone, the stakes are even higher. The therapeutic index for methadone in opioid-naïve patients can be as low as 2:1. That means the dose that relieves pain is almost the same as the dose that stops breathing. A switch to a generic with slightly higher bioavailability could cause respiratory arrest. A switch to one with lower absorption? Pain returns. Addiction relapse follows.

Patients with epilepsy, heart conditions, or psychiatric disorders are especially vulnerable. One mother in Ohio described how her 12-year-old son started having seizures after his pharmacy switched his phenytoin brand. The doctor had to run emergency blood tests, adjust the dose, and switch him back - all because the generic wasn’t absorbed the same way.

It’s not just about the drug. It’s about the person. Age, weight, liver function, diet - all affect how a drug is absorbed. A change in generic can throw off that balance. And unlike a headache pill, you can’t just take an extra tablet if it doesn’t work.

What Should You Do?

If you take an NTI drug, here’s what you need to know:

- Ask your doctor if your medication is an NTI drug. If it is, ask whether switching generics is safe for you.

- Never switch without talking to your prescriber. Even if the pharmacy says it’s "equivalent," they don’t know your history.

- Monitor closely. If you switch, your doctor should check blood levels within days. For warfarin, that means an INR test. For phenytoin, a serum level check.

- Keep a list of every medication you take - brand name and generic - and share it with every provider.

- Know your symptoms. If you feel dizzy, confused, nauseous, or unusually tired after a switch, call your doctor. Don’t wait.

Some states have rules that block automatic substitution for NTI drugs. North Carolina, for example, requires prescriber approval before switching. But many don’t. That means the decision is left to the pharmacy - and the pharmacy’s bottom line.

The Bigger Picture

The push for generics is understandable. They save billions. But for NTI drugs, cost-cutting can’t come at the cost of safety. The FDA acknowledges this. In recent years, they’ve recommended tighter bioequivalence standards - but they haven’t enforced them. The debate continues. Until then, the burden falls on patients and doctors to stay vigilant.

There’s no universal answer. Some people switch without issue. Others don’t. But for NTI drugs, the rule should be simple: if the margin is thin, don’t risk it.

Are all generic drugs unsafe for NTI drugs?

No, not all generics are unsafe. Some patients switch without any issues. But the problem is unpredictability. Two people can take the same generic version of warfarin - one stays stable, the other bleeds. Because absorption varies between brands and even between batches, you can’t assume safety. That’s why physician oversight is critical.

Can pharmacies refuse to switch my NTI drug to a generic?

Yes, if your doctor writes "Do Not Substitute" on the prescription, the pharmacy must honor it. In some states, laws require this for NTI drugs. Even where it’s not required, pharmacists can refuse if they believe it’s unsafe. Always ask your doctor to include this note if you’re concerned.

Why does the FDA allow 80-125% bioequivalence for NTI drugs?

The FDA uses the same standard for all drugs because it’s easier to regulate. Changing it would require new testing protocols, more data, and higher costs for manufacturers. While experts agree the standard is too loose for NTI drugs, the agency hasn’t yet updated its policy. Some argue that tighter limits would make generics too expensive - but others say patient safety should come first.

How do I know if my drug is an NTI drug?

Common NTI drugs include warfarin, phenytoin, lithium, digoxin, theophylline, cyclosporine, and methadone. Ask your pharmacist or doctor. You can also check the FDA’s list of drugs with narrow therapeutic indices. If your drug requires regular blood tests, it’s likely an NTI drug.

What should I do if I notice changes after switching generics?

Contact your doctor immediately. Don’t wait. Document when you switched, what symptoms you’re feeling, and whether you’ve changed anything else (diet, other meds, sleep). Your doctor may need to check blood levels, switch you back, or adjust your dose. Even small changes in how you feel can signal a dangerous shift in drug levels.

If you’re on an NTI drug, your medication isn’t just a pill. It’s a precise tool. And like any precision tool, you can’t swap parts without knowing the consequences.

Rob Turner

February 11, 2026 AT 19:31Man, this post hit different. I’ve been on warfarin for 7 years, and my INR’s been stable as hell-until my pharmacy switched me to a generic without telling me. I didn’t feel anything at first, but then I got dizzy during my morning walk. Turned out my INR was 5.8. Scary stuff. Not all generics are evil, but the system’s rigged to cut corners. I’m lucky I caught it.

Also, side note: if your doc doesn’t monitor you after a switch, find a new one. Period.

christian jon

February 12, 2026 AT 17:13Oh, FOR THE LOVE OF GOD, PEOPLE! THIS IS WHY WE CAN’T HAVE NICE THINGS! The FDA? They’re not regulators-they’re corporate lapdogs! They let generics slide through with an 80–125% window?! That’s not science-it’s a casino! And now we’re supposed to trust some guy in a white coat at CVS who’s got 17 seconds to fill a prescription?!

I’ve seen it happen. My cousin, a 58-year-old nurse with bipolar disorder, went from lithium levels of 0.8 to 1.4 in 48 hours after a switch. She ended up in the psych ward. They didn’t even test her! They just said, ‘It’s bioequivalent.’ Bioequivalent?! My dog’s poop is bioequivalent to hers after Taco Tuesday!

WE NEED TO BAN GENERIC SUBSTITUTION FOR NTI DRUGS. FULL STOP. NO MORE ‘IT’S FINE.’ NO MORE ‘IT’S CHEAPER.’ THIS ISN’T A MARKET-IT’S A LIFE.

Autumn Frankart

February 13, 2026 AT 21:45They’re not just swapping generics. They’re swapping your life for a profit margin. I’ve read reports-real ones, not the FDA propaganda-that say big pharma owns the generic manufacturers too. It’s all the same companies. Brand name? Owned by Pfizer. Generic? Owned by Pfizer. They just change the label. And now they want you to believe it’s ‘equivalent’?!

They’ve been doing this since the 80s. Phenytoin? That was a massacre. People died. And what happened? Nothing. No lawsuits. No accountability. Just another ‘oops’ in the system.

They’ll say, ‘But we have monitoring!’ Yeah, right. Who’s gonna pay for monthly blood draws when your insurance won’t cover it? You’re stuck. You’re a number. And they’re laughing all the way to the bank.

Pat Mun

February 14, 2026 AT 17:30I’m a nurse practitioner, and I’ve been saying this for years: NTI drugs are not like antibiotics or statins. You can’t treat them like commodities. I had a patient on lithium for 12 years-stable, happy, working, parenting. Switched generics. Three days later, she was trembling, confused, and couldn’t hold a spoon. Her lithium level? 1.8. Toxic. She didn’t even know she’d been switched. The pharmacy didn’t call. Her doctor didn’t know. It was a perfect storm of negligence.

Here’s what I tell my patients: If your med requires blood tests, don’t let anyone swap it without your explicit approval. And if your pharmacist says, ‘It’s the same,’ ask them to show you the bioequivalence study. Most can’t. And that’s the point.

It’s not about being anti-generic. It’s about being pro-safety. We can do better. We have to.

Skilken Awe

February 15, 2026 AT 17:22Oh, so now we’re treating NTI drugs like bespoke surgical instruments? ‘Oh no, the generic has 12% higher bioavailability!’ Please. The body isn’t a lab rat. It adapts. You think your liver can’t handle a 10% fluctuation? That’s like saying your immune system can’t handle a cold because the virus strain changed.

Most of these ‘stories’ are anecdotal noise. People panic. They blame the pill. Meanwhile, they started drinking more grapefruit juice, stopped sleeping, or switched to a new thyroid med. But nope-must be the generic. Classic confirmation bias.

Also, ‘FDA is corrupt’? Bro. They’re the only thing keeping snake oil off the market. Stop the drama. If you’re stable, don’t switch. If you’re not, go back to brand. Simple.

andres az

February 16, 2026 AT 08:10NTI drugs? Yeah, whatever. The whole system’s a scam. Big Pharma invented ‘narrow therapeutic index’ to scare people into buying expensive brand names. They know generics are fine. But if you convince people they’re dangerous, you keep your monopoly. It’s pure capitalism. No one dies from switching warfarin generics. People die from not taking their meds because they can’t afford them.

Stop being scared. Stop paying extra. If you’re stable on a generic, stay on it. If you’re not, switch back. It’s not rocket science. It’s just money.

Alyssa Williams

February 17, 2026 AT 23:13Hey everyone-I just want to say thank you for this thread. I’ve been on phenytoin for 15 years. Switched generics once. Seizure-free for 12 years. Then, one day, I had a minor one. Not a grand mal. Just a moment of zoning out. I called my neurologist. He checked my levels. Down 25%. We switched back. I’m fine now.

But here’s what I learned: I didn’t know I’d been switched. The pharmacy didn’t tell me. My doctor didn’t ask. I only caught it because I was paying attention. So please-if you’re on an NTI drug, be your own advocate. Ask questions. Track your symptoms. Write them down. Your life depends on it. You’re not being paranoid. You’re being smart.

Jack Havard

February 19, 2026 AT 08:36So let me get this straight. You’re telling me a drug with a 2:1 therapeutic index can’t be safely substituted because of a 45% bioequivalence window? That’s not a flaw in the system-that’s a flaw in the math. If the window is that narrow, then the drug shouldn’t be approved in the first place. Or we need to redesign the entire testing protocol.

But no. We just keep letting people switch and hope for the best. Meanwhile, the FDA collects fees from the manufacturers and calls it ‘efficiency.’

I’m not against generics. I’m against lazy regulation.

Gloria Ricky

February 20, 2026 AT 02:21My grandma’s on digoxin. Switched to generic last year. No issues. She’s 82, lives in a small town, and her pharmacist has known her since 1998. He called her doctor before switching. They tested her levels. She’s fine.

Not every switch is a disaster. Context matters. The system isn’t broken-it’s being misused. Pharmacies in big cities rush. Rural ones? They know their patients. Maybe we need more human oversight, not less.

Also, if you’re scared, ask for the brand. Most places will honor it. Even if it costs more. You’re worth it.

Stacie Willhite

February 20, 2026 AT 21:42I just wanted to say: if you’re reading this and you’re on an NTI drug, you’re not alone. I’ve been on lithium since I was 19. I’ve switched generics twice. Both times, I got shaky and nauseous. Both times, I called my doctor immediately. Both times, we switched back.

It’s not about being scared. It’s about being informed. Your body knows when something’s off. Trust it. Keep a journal. Write down how you feel every day. Share it with your provider. You’re not being dramatic. You’re being responsible.

And if someone tells you ‘it’s fine,’ ask them: ‘Have you ever had a patient bleed out because of a generic switch?’ If they say yes, listen. If they say no, ask why they’re so sure.

Jason Pascoe

February 21, 2026 AT 04:28From Australia-we have similar rules here. NTI drugs can’t be substituted without prescriber approval. It’s not perfect, but it’s better than nothing. I’ve seen patients panic when they see a different pill. But once you explain that the active ingredient is the same, and the difference is in fillers, most calm down.

The real issue? Lack of communication. Pharmacies don’t inform. Doctors don’t check. Patients don’t ask. It’s a system failure, not a drug failure.

Maybe we need a sticker on the bottle: ‘This is an NTI drug. Monitor closely after switch.’ Simple. Clear. Effective.

Annie Joyce

February 23, 2026 AT 02:16As a pharmacist who’s worked in both chain and independent pharmacies-I’ve seen both sides. Chain pharmacies? They switch automatically. No call. No warning. Just ‘here’s your new pill.’ Independent? We call the prescriber. We check the chart. We tell the patient. It takes 5 extra minutes. But it saves lives.

Some generics are better than others. Some batches are off. It’s not black and white. But if you’re on warfarin or lithium? Don’t let a robot decide your dose. Ask for the brand. If you can’t afford it, ask for help. There are programs. There are charities. You don’t have to suffer.

And to the people saying ‘it’s all hype’? You’ve never held someone’s hand while they bled from the gums because their INR hit 7. Do that once. Then come back and tell me it’s not real.

Suzette Smith

February 23, 2026 AT 19:51Wait, so you’re saying generics are dangerous? But what about all the people who take them and don’t have problems? Maybe it’s not the drug-it’s the person. Maybe you’re just sensitive.