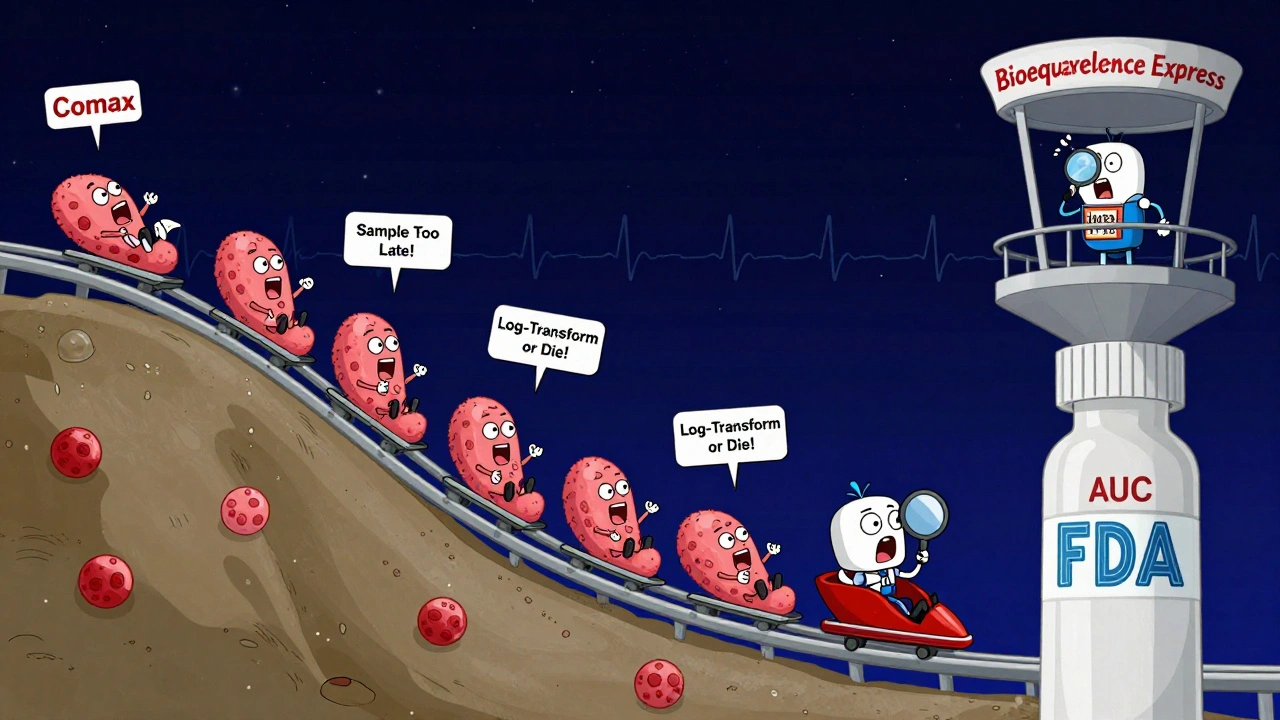

When a generic drug hits the shelf, you might assume it’s just a cheaper copy of the brand-name version. But behind that simple label is a rigorous science built on two numbers: Cmax and AUC. These aren’t just lab terms-they’re the gatekeepers that decide whether a generic drug is safe and effective enough to replace the original. If these numbers don’t match closely enough, the generic doesn’t get approved. And that’s not just bureaucracy-it’s patient safety.

What Cmax Tells You About Drug Absorption

Cmax stands for maximum plasma concentration. It’s the highest level of a drug your bloodstream reaches after you take it. Think of it like the peak of a wave. If you take a painkiller, Cmax tells you how strong that hit will be. Too low, and it won’t work. Too high, and you risk side effects-especially with drugs that have a narrow safety window, like blood thinners or seizure medications.

For example, if a brand-name drug hits a Cmax of 8.1 mg/L, the generic must land within 80% to 125% of that-so between 6.5 and 10.1 mg/L. That’s the rule. But it’s not just about the number. When that peak happens matters too. The time to reach Cmax, called Tmax, helps show how fast the drug gets into your system. A generic that reaches peak concentration 30 minutes faster might be fine for a headache pill, but dangerous for a drug that needs slow, steady absorption.

Regulators require detailed blood sampling-often 12 to 18 time points over several hours-to catch that peak accurately. Miss the sampling window, and you might think the drug is slower than it really is. That’s why studies are designed with tight timing, especially for fast-absorbing drugs. If you sample too late, you’ll underestimate Cmax. And if you underestimate it, you might wrongly approve a drug that doesn’t work as well.

What AUC Measures: The Full Picture of Exposure

If Cmax is the peak, AUC is the whole wave. AUC stands for area under the curve-the total amount of drug your body is exposed to over time. It’s measured in mg·h/L. This number tells you how much of the drug your body actually absorbs and keeps circulating. For drugs that work over hours-like antibiotics or antidepressants-AUC is the most important number. Even if the peak is a little off, if the total exposure is right, the drug will still work.

Imagine two people take the same dose of a drug. One gets a sharp, high peak but the drug clears fast. The other gets a lower peak but the drug sticks around longer. Their Cmax might look different, but if their AUC is nearly identical, their overall effect will be the same. That’s why regulators require both measurements. One tells you how fast the drug acts. The other tells you how long it works.

Studies typically measure AUC from the time the drug is taken until it’s almost gone (AUC(0-t)) or until it’s completely cleared (AUC(0-∞)). For some long-acting drugs, they even use AUC(0-72h) to capture the full exposure window. The key is consistency: the same method must be used for both the brand and the generic. Otherwise, the comparison is meaningless.

The 80%-125% Rule: Why It Exists

There’s a reason the standard for bioequivalence is 80% to 125%. It’s not arbitrary. This range came from decades of data and statistical modeling. In the early 1990s, regulators realized that differences smaller than 20% in drug exposure rarely led to real-world changes in how patients felt or what side effects they had. That’s why they settled on a 90% confidence interval around the geometric mean ratio of generic to brand-name drug.

Here’s how it works: If the generic’s AUC is 95% of the brand’s, that’s within limits. If it’s 78%, it fails. Same with Cmax. Both have to pass. One can’t save the other. A drug might have perfect AUC but a Cmax that’s 130% of the original. That’s a no-go. Why? Because a higher peak could mean more side effects-even if the total exposure is fine.

This rule applies to most drugs. But there are exceptions. For drugs with a narrow therapeutic index-like warfarin, lithium, or levothyroxine-small changes can be dangerous. Some regulators, like the EMA, allow tighter limits (90%-111%) for these. Others, like the FDA, use a method called scaled average bioequivalence for drugs with high variability between people. That means if the brand drug behaves very differently from person to person, the acceptable range for the generic can widen slightly. But even then, the core idea stays the same: exposure must be predictable and safe.

Why Both Metrics Are Non-Negotiable

Some people think if AUC matches, Cmax doesn’t matter. That’s a dangerous myth. Take a drug like carbamazepine, used for epilepsy. If the generic has the same total exposure (AUC) but peaks too fast, it could trigger seizures. Or consider a stimulant like methylphenidate. A higher Cmax might cause jitteriness or high blood pressure-even if the total dose is the same.

Regulatory agencies don’t just look at numbers. They look at what those numbers mean for patients. The FDA’s 2013 guidance says bioequivalence isn’t just about chemistry-it’s about clinical outcomes. And decades of real-world data back that up. A 2019 analysis of 42 studies in JAMA Internal Medicine found no meaningful difference in effectiveness or safety between approved generics and brand-name drugs. That’s because they passed the Cmax and AUC tests.

It’s not about being identical. It’s about being equivalent. Two drugs can have slightly different shapes on the concentration-time curve and still be bioequivalent. But if the peak or the total exposure strays too far, the risk isn’t theoretical. It’s real.

How Studies Are Done-and Why They Sometimes Fail

Bioequivalence studies are usually done in 24 to 36 healthy volunteers. They’re crossover studies: each person takes the brand drug in one period, then the generic in another, with a washout period in between. Blood is drawn frequently-every 15 to 30 minutes at first, then less often-as the drug rises and falls in the bloodstream.

The most common reason studies fail? Poor sampling during the absorption phase. If you don’t collect blood samples in the first hour or two, you might miss the true Cmax. Industry data shows about 15% of failed studies are due to this. Another issue? Using nominal times instead of actual times. If a sample was supposed to be taken at 2 hours but was actually drawn at 2 hours and 15 minutes, you can’t just pretend it was on time. The math gets thrown off.

Analysts use specialized software like Phoenix WinNonlin to process the data. They log-transform the AUC and Cmax values because these numbers don’t follow a normal bell curve-they follow a log-normal distribution. If you don’t transform them, your statistics are wrong. And if your statistics are wrong, your approval is invalid.

What’s Changing-and What’s Not

The science behind Cmax and AUC has held up for over 40 years. But the world is changing. For complex drugs-like extended-release tablets or patches-standard AUC and Cmax might not tell the whole story. That’s why the FDA is exploring partial AUC measurements for drugs with multiple absorption peaks. For example, a pain patch might release drug slowly over hours, then have a small secondary peak. Total exposure might look fine, but if that second peak causes side effects, regulators need to see it.

For narrow therapeutic index drugs, tighter limits are being considered. The EMA already recommends 90%-111% for levothyroxine. The FDA is watching closely. But even with new tools like modeling and simulation, Cmax and AUC remain the foundation. As FDA expert Robert Lionberger said in 2022, they’re the gold standard because they’ve been proven, tested, and trusted for decades.

Today, over 1,200 generic drugs get approved in the U.S. each year. Almost all rely on Cmax and AUC. The global market for bioequivalence studies is worth over $2 billion and growing. Why? Because patients and doctors need to trust that a cheaper pill does the same job. And that trust comes down to two numbers.

What This Means for You

If you’re taking a generic drug, you don’t need to worry. If it’s approved, it passed the same tests as the brand. The system works. But if you’ve ever wondered why your doctor asked if you were on the brand or generic-now you know. It’s not about the name on the bottle. It’s about what’s happening inside your body. And that’s measured by Cmax and AUC.

These aren’t just lab results. They’re the invisible bridge between science and safety. And as long as people need affordable medicines, they’ll keep being the standard.

What does Cmax mean in bioequivalence?

Cmax stands for maximum plasma concentration-the highest level a drug reaches in your bloodstream after taking it. It tells you how fast the drug is absorbed and helps predict how quickly it will start working or cause side effects. For bioequivalence, the generic drug’s Cmax must be within 80%-125% of the brand-name drug’s.

What is AUC and why is it important?

AUC, or area under the curve, measures total drug exposure over time. It shows how much of the drug your body absorbs and how long it stays in your system. For drugs that need steady levels-like antibiotics or antidepressants-AUC is often more important than the peak. To be bioequivalent, the generic’s AUC must also fall within 80%-125% of the brand’s.

Why do both Cmax and AUC need to pass for bioequivalence?

Because they measure different things. Cmax shows how fast the drug enters your blood-critical for drugs where timing affects safety or effectiveness. AUC shows total exposure-key for drugs that work over time. If only one passes, the drug might work too fast, too slow, or cause side effects. Regulators require both to ensure the generic behaves like the original in real life.

What is the 80%-125% rule and where did it come from?

The 80%-125% range is the accepted bioequivalence limit for both Cmax and AUC. It was adopted in the early 1990s after statistical analysis showed that differences smaller than 20% rarely caused clinical differences. The range is symmetrical on a logarithmic scale, which matches how drug concentrations are distributed in the body. It’s used globally because it balances safety with practicality.

Are there exceptions to the 80%-125% rule?

Yes. For drugs with a narrow therapeutic index-like warfarin, lithium, or levothyroxine-small exposure changes can be dangerous. Some regulators, like the EMA, allow tighter limits (90%-111%) for these. For highly variable drugs, the FDA may use scaled bioequivalence, which allows wider limits based on how much the brand drug varies between people. But these are exceptions, not the rule.

How do regulators ensure accurate Cmax and AUC measurements?

Studies use frequent blood sampling-often every 15-30 minutes early on-to capture the true peak and full exposure. Actual sampling times are used, not scheduled ones. Data is log-transformed before analysis because drug concentrations follow a log-normal distribution. Specialized software like Phoenix WinNonlin is used to calculate values. Poor sampling, especially in the first 1-2 hours, is the most common reason studies fail.

Karl Barrett

December 3, 2025 AT 15:36Cmax and AUC aren't just regulatory checkboxes-they're the heartbeat of therapeutic equivalence. You can't just swap a pill and hope for the best. The body doesn't care about brand names, it cares about concentration curves. A 12% spike in Cmax might seem trivial, but for someone on lithium or warfarin? That's a trip to the ER waiting to happen. And AUC? That's the total dose your cells actually see over time. Miss that, and you're dosing blind. The 80-125% range isn't magic-it's statistical muscle built on decades of clinical outcomes. It's the difference between a drug that works and one that just looks the same on paper.

val kendra

December 4, 2025 AT 04:13So many people think generics are 'inferior' but this is why they're not. The system works. If your pill passed the Cmax/AUC test, it's doing the same job. No magic, no conspiracy-just hard science. Trust the data, not the label.

Alex Piddington

December 4, 2025 AT 14:03It's fascinating how such precise pharmacokinetic parameters govern something as fundamental as patient access to affordable medication. The rigor behind bioequivalence studies reflects a deep commitment to evidence-based medicine, even when commercial pressures exist. Regulatory agencies aren't merely gatekeepers-they're guardians of physiological integrity.

Shofner Lehto

December 5, 2025 AT 22:13Reading this made me realize how little most people know about what's actually in their medicine. The fact that blood samples are taken every 15-30 minutes during peak absorption is insane-but necessary. It's not just chemistry, it's biology under a microscope. We should be teaching this in high school.

Ben Choy

December 7, 2025 AT 12:41Love this breakdown. The 80-125% rule always seemed arbitrary until I saw the math behind it. Log-normal distribution, geometric mean ratios-it all clicks. And the part about nominal vs actual sampling times? That's the kind of detail that separates good science from sloppy work. Props to the labs that get this right.

Bill Wolfe

December 7, 2025 AT 13:24Let’s be real-most generic manufacturers cut corners. The FDA approves 1,200 drugs a year? That’s not diligence, that’s a conveyor belt. They’re letting generics slide because they don’t want to slow down the profit machine. You think they care if your seizure med peaks 130% higher? Nah. They care about the quarterly report. And don’t even get me started on how they use ‘scaled bioequivalence’ to excuse bad data. It’s corporate theater wrapped in scientific jargon.

Libby Rees

December 9, 2025 AT 10:41My grandma takes levothyroxine. She switched generics last year and her TSH stayed stable. No issues. I used to worry too. Now I know why: the system actually works. It’s not perfect, but it’s built on real data, not guesses. That’s more than most industries can say.

George Graham

December 10, 2025 AT 01:48As someone who’s watched a family member struggle with epilepsy meds, this hits home. I used to think generics were just cheaper versions. Now I know they’re scientifically validated clones. That’s powerful. The fact that regulators demand both Cmax and AUC means someone’s watching out for the little guy. Not all heroes wear capes-some work in labs with blood tubes and WinNonlin software.

Jake Deeds

December 11, 2025 AT 08:53It’s hilarious how people act like they’re so informed when they’ve never even read the FDA guidance on bioequivalence. You don’t get to have an opinion if you don’t understand log-transformed data. I’ve seen people on forums ranting about generics like they’re biochemists. Spoiler: they haven’t even opened a pharmacokinetics textbook. The 80-125% rule? It’s not a suggestion. It’s a law written in math. And if you don’t respect it, you’re not a patient-you’re a liability.

michael booth

December 11, 2025 AT 11:01It is imperative to underscore the significance of adhering to standardized sampling protocols in bioequivalence studies. The integrity of Cmax and AUC measurements hinges upon precise temporal alignment and the application of appropriate statistical transformations. Deviations from established methodologies introduce systemic bias and compromise the validity of regulatory conclusions. Therefore, the rigorous adherence to protocols is not merely procedural-it is ethically non-negotiable.

Rudy Van den Boogaert

December 12, 2025 AT 17:05I used to work in a pharmacy. People would come in and say 'I won't take the generic' because it's 'not the real thing.' I'd show them the FDA bioequivalence report. Most of them just shrugged. But one guy, old veteran, said 'If it passes the test, I'll take it.' That stuck with me. Science doesn't care about brand loyalty. It cares about what's in the blood.

Chad Handy

December 14, 2025 AT 14:55Everyone thinks generics are fine until it’s their kid on seizure meds or their spouse on blood thinners. Then suddenly they’re calling the doctor, demanding the brand. Hypocrisy. The data doesn’t lie. If the AUC and Cmax are within range, the drug is equivalent. But people need to feel like they’re paying more for something better. It’s not about safety-it’s about status. And that’s why the system still gets attacked by people who don’t understand it. We’ve turned medicine into a luxury brand. And that’s the real tragedy.

Emmanuel Peter

December 16, 2025 AT 06:42Wait, so you’re telling me a generic that hits 124% Cmax is approved but 126% isn’t? That’s a 2% difference. You’re telling me someone’s life hinges on a 2% fluctuation in a blood test? That’s not science, that’s bureaucracy with a PhD. And don’t even get me started on how they use ‘log-normal distribution’ to make simple math look like rocket science. This isn’t precision medicine-it’s statistical theater. You could literally swap a drug with 10% variation and no one would notice clinically. But the regulators need their boxes checked. Sad.

Dematteo Lasonya

December 16, 2025 AT 20:28My dad’s on warfarin. He’s been on the same generic for 8 years. No clots, no bleeds. I used to stress about it. Now I know why: the system works. Cmax and AUC aren’t just numbers-they’re the reason he’s still here. Thank you for explaining it so clearly.